Real-time thirsty

In this post, I show using a fictitious example why real-time systems are defined by their worst-case timing rather than their average-case timing.

Imagine you’re running a coffee shop – not the kind you find in Amsterdam, but one where they actually serve coffee. Your customers are generally in a hurry, so they just want to get a cup of coffee, pay and leave to catch their plane, train or automobile. To attract more customers and appeal to the Geek crowd, you name your coffee shop “Real-Time Thirsty” and promise an “Average case serving within one minute!”.

While you get many customers, you’re not getting the Geeks-in-a-hurry crowd you were expecting.

Average-case vs. worst-case timing

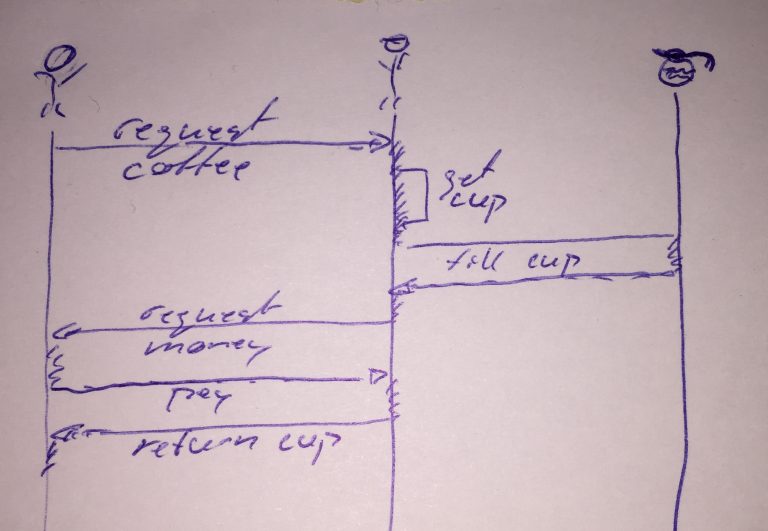

Fig. 1 shows the interaction needed to get a cup of coffee: the customer requests a coffee, the barista gets a cup, fills it, asks for money and gives the coffee to the customer. The whole exchange might take all of one minute in the average case – you’re keeping your promise, so why won’t the Geeks-in-a-hurry come?

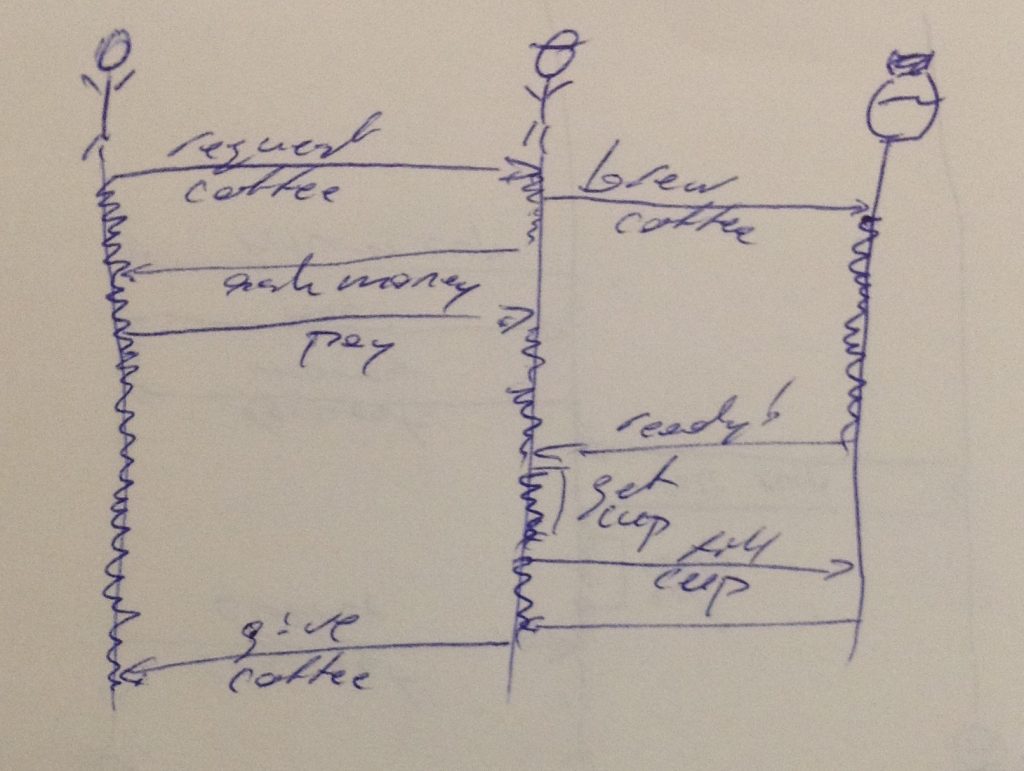

The problem happens when the coffee still needs to be brewed when the customer gets there: the barista happily accepts the order, starts brewing the coffee and asks the customer to pay. The customer, now expecting his coffee to arrive “any moment now” ends up waiting a full fifteen minutes for his coffee, misses his plane, train or automobile and is righteously pissed off (Pardon my French).

The Geeks, of course, know a real-time system when they see one, and can smell a “soft” system from a mile away. In your case, with your promise of an average-case serving time of one minute, they knew something was wrong when they saw the promise – whether you keep it or not.

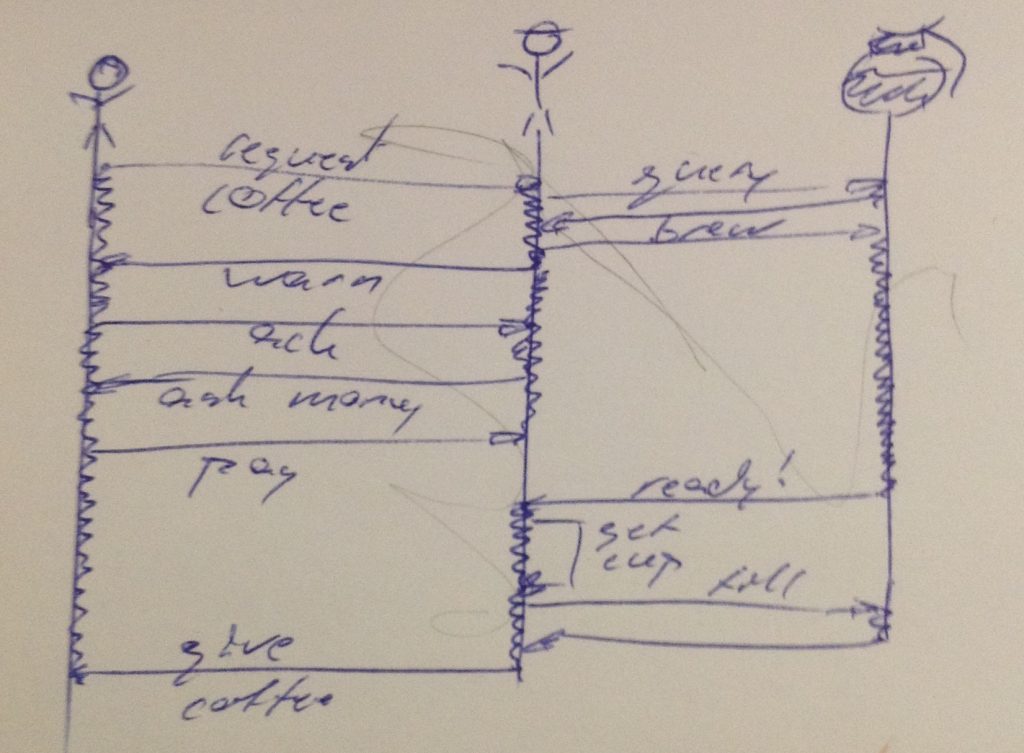

“Warn” if not ready – non-blocking state test

After being yelled at a few times, the barista has decided to warn the customer. This allows the customer to evaluate whether they will meet their deadline if they wait for coffee1.

In general, your customers are now fairly happy: the try to obtain a coffee and will be warned if they cannot be immediately served so they can go catch their plane, train or automobile, or do whatever else they want to do while waiting.

Now, some Geeks have started coming, but none of them are in both thirsty and in a hurry: some are thirsty and not in a hurry while others are in a hurry, but could forego their dose of caffeinated beverage if required to.

Redundancy

After observing the Geeks that are in a hurry but not all that thirsty for a while, you notice that some of them, when warned, go to one of your competitors to get their coffee. The coffee at your competitor is slightly more expensive, but Geeks-who-need-caffeine don’t seem to mind. After reading up on the subject a bit, you note that what they’re doing is implementing redundancy – which is something you could do yourself.

So, you decide to buy a second coffee machine and make sure one of them always has at least a cup of coffee in it. After running with it for a month, you notice that if you brew the first pot of coffee before opening the doors, you never run out of coffee throughout the day! Happy with these results, you change your sign to say “We always serve within one minute!”

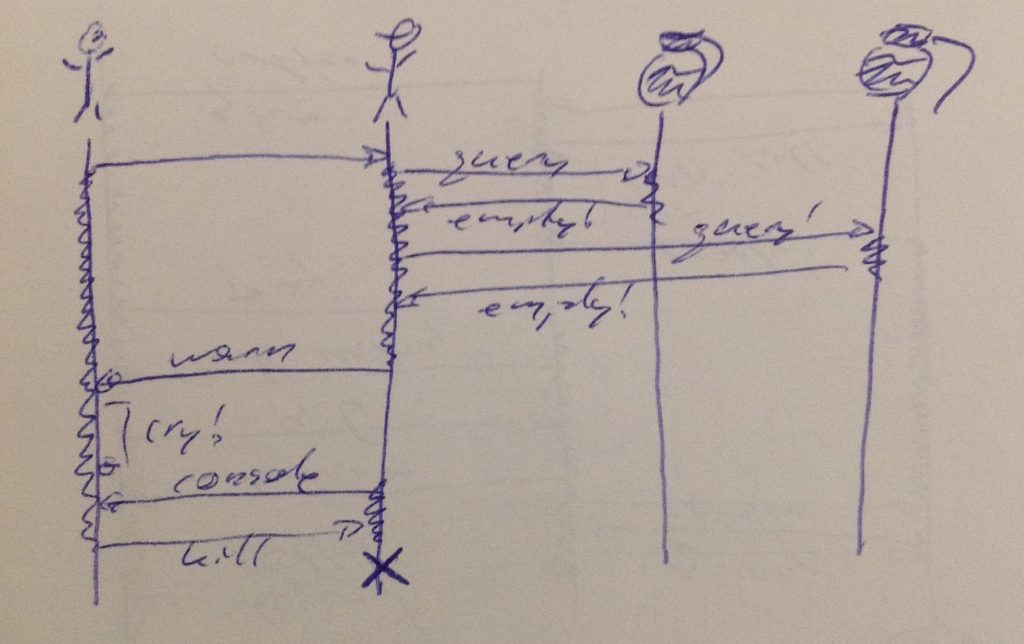

Catastrophe strikes: the scenario in Fig. 4 happens.

When the police arrives, you explain that that morning, just after you had changed your sign, a throng of Geeks arrived for coffee. All of them thirsty, caffeine-deprived and in a hurry. While you were able to serve the first group of twenty Geeks from the first pot and the second group of twenty Geeks from the second pot, your first pot hadn’t finished brewing in time to serve the forty-first customer. The barista tried to warn him, but the Geek – being caffeine-deprived and in a hurry – started to cry in desperation. When the barista tried to console the Geek with a “there-there, the coffee will be ready in just a few seconds” the Geek was enraged by the extra delay – and killed the barista.

After having taken your statement, the police officer rightly takes you into custody and explains that a caffeine-deprived Geek, while extremely dangerous, is still allowed to kill whomever caused the caffeine deprivation in such circumstances: a real-time post-condition was not met – hence, you, not the Geek, are responsible for the death of the barista.

A somewhat calmer Geek then explains your mistake: while brewing more pots reduces the frequency of worst-case-time performance, it does not reduce the worst-case time itself. Your worst-case time was still fifteen minutes.

Pouring your coffee faster would have reduced the average time, but would have done nothing for the worst case. Brewing smaller pots, on the other hand, would have reduced the worst-case time (but increased the frequency of their occurrence).

-

In code, this would be a

tryAcquirefunction that returnstrueif the resource is acquired andfalseif not. ↩