ICS Security: Current and Future Focus

The flurry of DNP3-related vulnerabilities reported to ICS-CERT as part of Automatak’s project Robus seems to have subsided a bit, so it may be time to take a look at where we are regarding ICS security, and where we might be going next.

Of course, I’ll only look at communications protocol security in this context: low-tech attacks on the grid1 is outside the scope of this article. In stead, I will take a look at two questions: why the focus on DNP3, and what else could they, and should they, be looking at.

The current focus on DNP3

There are two questions we can ask about the current focus on DNP3: why should we focus on DNP3?, and why did Crain and Sistrunk focus on DNP3? But before we ask those questions, we should get a quick idea of what DNP3 is.

DNP3 in a nutshell

DNP3 is an immensely complex protocol. The IEEE standard that defines it, IEEE Std™ 1815-2012 is over 700 pages long and still leaves parts of the standard to the imagination of the implementer – which is why the the DNP3 Technical Committee members write Application Notes and Technical Bulletins which are then debated in bi-weekly telecon meetings and in lengthy E-mails which continue through holidays, week-ends and well into the night, come hell or high water.

DNP3 also has a long history, dating back to “before rocks were old”2 and which is partly described on the DNP user’s group’s website.

This means that in order to implement DNP3, you need a lot of code. One partial implementation of DNP3 is OpenDNP33, which for the benefit of this post I downloaded from GitHub and ran cloc on:

691 text files.

684 unique files.

40 files ignored.

http://cloc.sourceforge.net v 1.55 T=4.0 s (162.5 files/s, 22578.0 lines/s)

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Language files blank comment code

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------

C++ 244 6039 6101 21064

XSLT 2 57 456 12515

C/C++ Header 258 5081 9196 11838

HTML 1 16 0 3391

XML 5 34 205 2341

Java 90 660 2713 1824

m4 13 190 15 1409

ASP.Net 2 442 0 1133

C# 27 265 1488 1102

make 3 26 3 341

MSBuild scripts 3 0 21 198

Scala 1 24 0 114

Bourne Shell 1 1 0 9

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------

SUM: 650 12835 20198 57279

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------

In over 57,000 lines of code, there’s bound to be a bug or two – even if only half of them actually implement DNP3, there’s still bound to be a bug or two in there that may affect device performance.

Why should we focus on DNP3?

-

DNP3 is very widely used in the industry

-

DNP3 is one of the few SCADA protocols that actually has security-related features

-

DNP3 is well-defined

-

DNP3 has a very active, receptive and open technical committee with very well-hearsed members that dedicate a lot of time and effort to making the protocol better, and better understood

In North America, DNP3 is used by the vast majority of utilities and supported by a large number of devices (probably the majority as well, but the installed base is huge and very old, so I won’t venture to asserting that it is a majority).

DNP3 is one of few SCADA protocols that have any security-related features – namely Secure Authentication. Most SCADA protocols work without any security at all.

DNP3 is well-defined, so if anything is found with the protocol itself (which has not been the case so far) it can be fixed. Devices are tested for compliance using compliance tests published by the DNP3 User’s Group. They come with a machine-readable Device Profile which states what a device can and cannot do, which parts of the standard it supports and to what extent, and which version of the compliance tests was used to test it.

The technical committee is security-aware. Its members know what they’re doing and are very actively seeking out issues with the protocol and user’s understanding of the protocol. For example, as a response to the Crain-Sistrunk vulnerabilities, the Technical Committee drafted an Application Note which is publicly available and which describes how one should go about validating incoming DNP3 data.

This means that

-

finding security issues is likely because of the large amount of code needed to implement the protocol

-

finding security issues will have a positive impact on the safety and security of a critical part of the infrastructure throughout North America

-

finding security issues is likely to lead to a fix of those security issues (because the user-base of the protocol is active and the technical committee is security-aware and inclined to be receptive)

-

security issues are likely to be the result of implementation issues rather than specification issues (because the technical committee is both security-aware and technically savvy, as well as pragmatic w.r.t. what the standard should look like)

Why did Crain and Sistrunk focus on DNP3?

I see two obvious reasons why Adam Crain and Chris Sistrunk would focus their efforts on DNP3:

-

Adam Crain wrote a large part of the OpenDNP3 stack and makes money off it.

Part of his efforts in looking for security bugs stems from debugging OpenDNP3 -

Both Adam Crain and Chris Sistrunk work in the field of the Smart Grid.

DNP3 is an important (i.e. widely-used) SCADA protocol that they both know well. Additionally, Chris Sistrunk has access to a wide variety of devices he can run tests on.

There are also a few less obvious, and perhaps less important, issues to consider:

-

DNP3 is a large and complex protocol. There are bound to be bugs in any implementation (so this is relatively low-hanging fruit).

-

Security issues have not been taken particularly seriously in the smart grid historically.

From Adam’s tweet concerning two posts on this blog:

2 posts from @blytkerchan about impact of #DNP3 vulns:http://t.co/MNpGBJxCQShttp://t.co/rA8Rf62lyV

— Code Monkey Hate Bug (@jadamcrain) January 5, 2014

Wake up NERC!

one might surmise he is somewhat frustrated with this state of affairs

- Disclosing these issues has lead to the Aegis Consortium, which will pay for the continued development of the fuzzing tool used to test the DNP3 stacks and devices – and will therefore pay for its developers’ livelihood for the foreseeable future.

This is by no means intended to be cynical: I think his apparent frustration with the lack of interest in security is justified, and I think making money off one’s own effort is nothing anyone should be ashamed of, or consider shameful in someone else – as long as those efforts are honorable.

In the case of Crain and Sistrunk, I believe they uphold a very high standard of “honorable” in terms of so-called “white hat hacking”. So far, they have done everything right:

- they have practiced “responsible disclosure”:

- they have contacted the DNP3 Technical Committee with their findings, without specifically naming any vendors to the vendors on the committee

- they have contacted ICS-CERT with their findings, providing the necessary information to the vendors to fix their problems free of charge

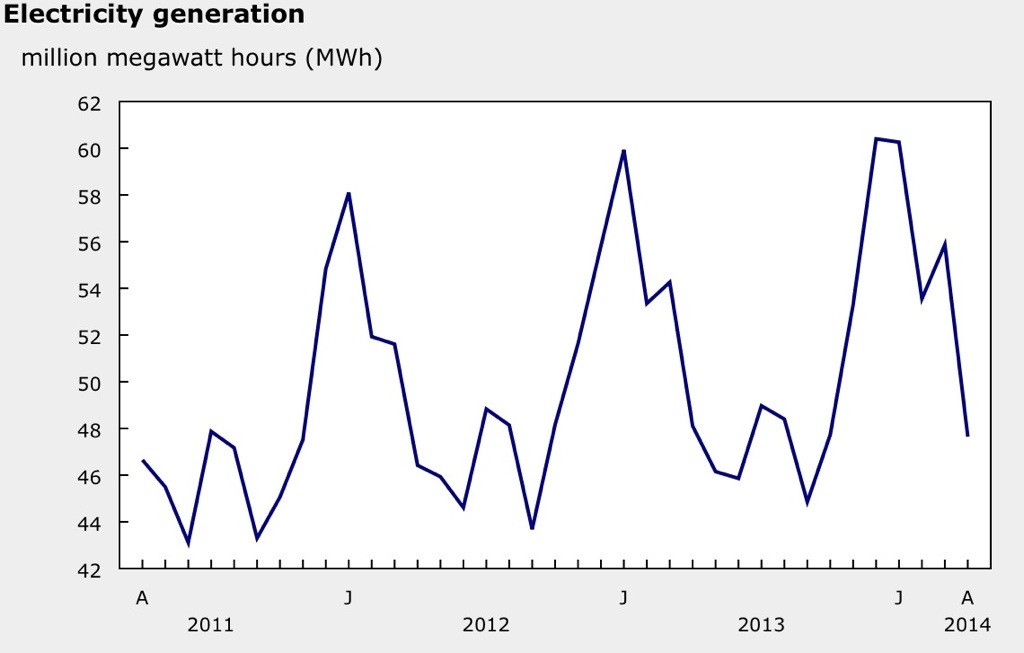

- their smart fuzzer tool was on,y made available after vendors had had a chance to fix their implementations and utilities had had a chance to deploy them though the time to deploy the fixes was very short: due to power consumption cycles, every time is not necessarily a good time to plan an outage to update firmware, as this chart from Statistics Canada illustrates:

- their smart fuzzer tool is available to vendors (though not for free)

They have all the information they need to attempt to extort money from vendors, sell vulnerabilities on the black market to the highest bidder (as zero-day exploits), etc. but, as far as I can tell, have done none of that but have taken the (rather less lucrative, but far more ethical) path of responsible disclosure all the way.

- they have been careful to protect the reputations of all involved:

- they have made it very clear that the problems they have found so far are implementation problems, not protocol problems

- they have made themselves available to the DNP3 Technical Committee, to help draft documentation to prevent future vulnerabilities, but have made their detailed findings available only to non-vendor members of the committee (so no vendor knows of the vulnerabilities of other vendors, which would cause conflicts of interest)

- they do not publish the names of affected vendors/devices until the ICS publishes the advisory, at which time the vendor will have had time to prepare a response

What’s next?

Among the protocols that are also often used in critical infrastructure, a few stand out:

- Modbus (modicon)

Widely used, old, fairly simple, but often implemented ad-hoc. There are bound to be security issues and robustness issues to be found with a smart fuzzer. - IEC 61850 and GOOSE

Complex, widely used (especially in Europe). Excellent candidate for fuzzing - IEC 60870-5-101/104

The protocol DNP3 was originally spun off from. Fairly widely used, as complex as DNP3, similar in design to DNP3. - any of the large number of home-grown vendor-specific, device-specific protocols

a “metasploit for ICSs” would be wonderful to have

Some of these are already on the list of protocols the Aegis people intend to look at (their choice of IEC 60870 protocols is 60870-6 rather than 60870-5). I would be surprised if they don’t find anything interesting – which means there should be vulnerabilities being discovered by this project for several years to come.

In the interest of full disclosure, I should indicate (at least in this page) that I work, among others, for Eaton’s Cooper Power Systems EAS, which is the manufacturer of one of the devices and vendor of another software solution which were subject to these advisories. I was involved in the response to those advisories. I am also a (non-voting) member of the DNP3 Technical Committee.

That said, the opinions I expressed in this article are my own. I am not getting paid for writing this and, to the best of my knowledge, everything in this post is truthful.

Edits

2014-07-10: link to the DNP3 Application Note corrected – thanks to Chris Sistrunk for pointing out the broken link

2014-07-10: hand-drawn illustration of the balloon hack replaced with one made in SketchUp. Thanks to Cadyou user Anthea16 for sharing a beautiful drawing of a pylon

-

E.g. letting two helium-filled balloons up with a wire between them, under a high-voltage power line, in order to cause a short between the phases ↩

-

this is a direct quote from one of the earliest members of the DNP3 Technical Committee, but I don’t remember which one)) ↩

-

I say “partial” because they don’t implement DNP3 SAv5 yet, and there’s probably some other features missing as well – I don’t know much about this particular implementation. ↩