Coaching and problem solving

I am not a teacher. According to my wife, who is a professor at law and therefore knows a thing or two about teaching, I am really, definitely not a teacher. I may have taught the occasional workshop and may try to explain things from time to time, but who am I to argue with my wife? I do find myself in the position of having to explain things a lot, though, and with today’s teleconferencing technologies, I find myself explaining to an ever-wider audience. The people on the other end of the connection are generally not novices: we share a common vocabulary and a common way of thinking about problems that makes it easier to convey whatever message I’m trying to convey. For my wife, that would be the equivalent of talking to graduate or post-graduate students. Sometimes, though, I don’t get my point accross, so I decided to read up on teaching.

Most of the explaining I do revolves around knotty problems in some complex part of a system, or the design of some new complex system as part of a system of systems. Sometimes the discussion goes into cryptography, and sometimes the discussion goes into FPGA firmware design or the intricacies of a high-precision time synchronization mechanism. Because the person at the other side of the connection is almost always a software or firmware engineer who’s already been through years of university and usually has several years of experience in their field, when I need to explain something it’s never something trivial. I wouldn’t need to explain something trivial: I’d just point them to where they can find the answer. So the only explaining I end up doing is about something that I have spent a significant amount of time on, and they have not because they were doing other things which they could explain to me. The more time I have spent on the particular issue, and the less they have, the more difficult the explaining becomes: our frames of reference are further apart and our language is less alike. As this usually happens in the context of trying to solve some problem, the problem may get worse while we get more frustrated.

To solve problems in a new area, you need to learn about the area, learn to understand the problem, and learn how to validate and verify the solution to the problem. You need to learn all this before you can actually go ahead and solve the problem by writing code, writing test cases, etc. This incurs a cognitive load that makes problem solving more difficult. This realization guided my search for reading material on the subject. I got lucky.

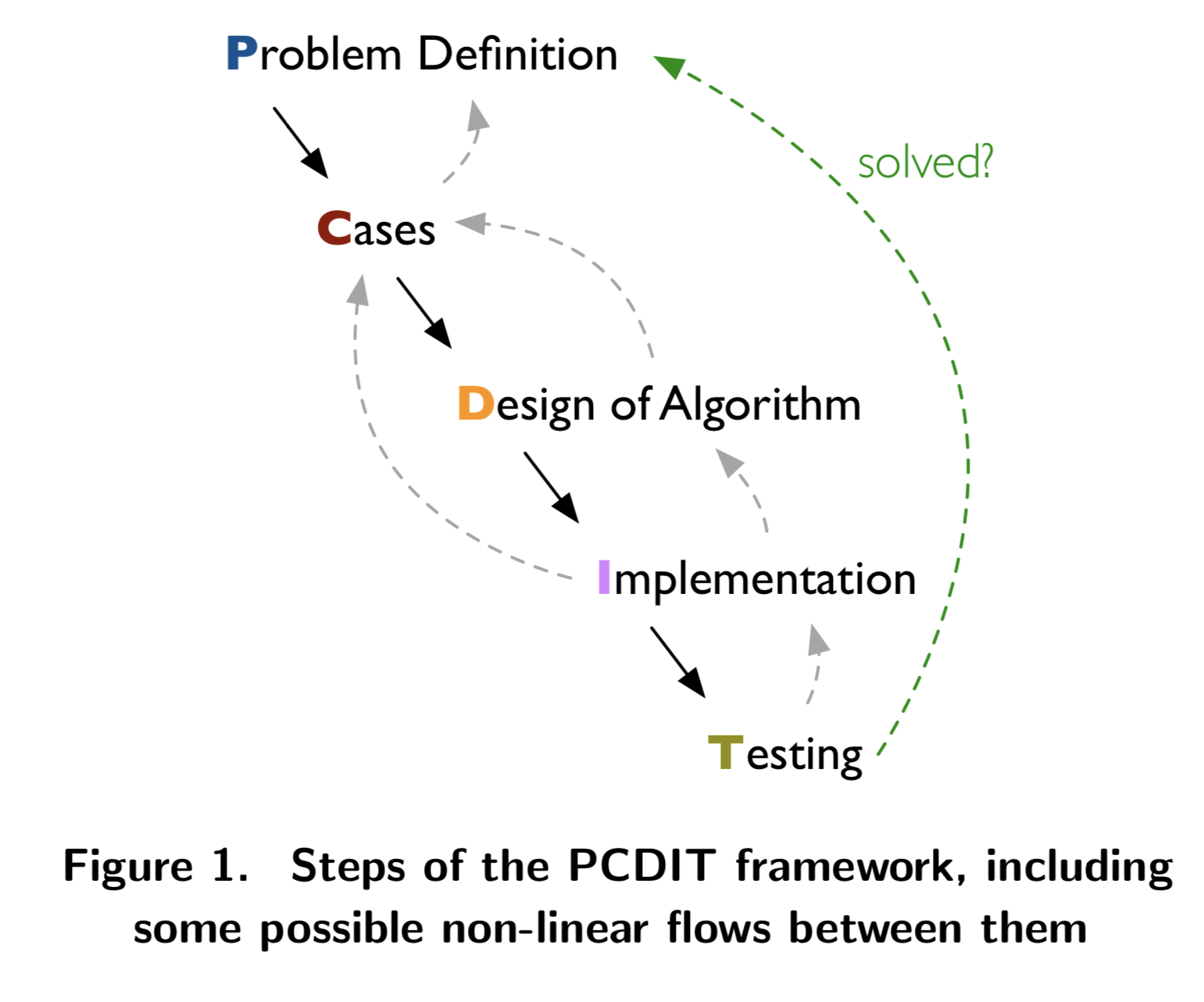

In a recent pre-print article on a new teaching framework, Oka Kurniawan, Cyrille Jégourel, Norman Tiong Seng Lee, Matthieu De Mari, and Christopher M. Poskitt write about teaching problem-solving skills to novice programmers. Novice programmers don’t usually get presented with very complex issues, but the framework they propose has some good ideas to help solve more complex issues as well. The framework consists of five steps:

In a recent pre-print article on a new teaching framework, Oka Kurniawan, Cyrille Jégourel, Norman Tiong Seng Lee, Matthieu De Mari, and Christopher M. Poskitt write about teaching problem-solving skills to novice programmers. Novice programmers don’t usually get presented with very complex issues, but the framework they propose has some good ideas to help solve more complex issues as well. The framework consists of five steps:

- Problem definition

- Cases

- Design of algorithm

- Implementation

- Testing

The framework is iterative at every step: once you’ve defined the problem, you think of a few cases, which you then use to refine the problem definition. Once you’ve refined the problem definition and found enough cases to be able to test the solution with, you can design an algorithm to solve the problem. Once you’ve done that, you can implement it, refining the design as needed. The implementation obviously needs to address the cases, which you can verify by testing. Once you’ve implemented both the solution and the tests, you can check whether the problem is solved and, if not, iterate through the process again until it is fixed.

The general idea here is to develop an understanding of the problem and the solution before any code is actually written, creating a mental model of the problem space and developing the ability to reason about the problem and its solution. The intent is to reduce the “cognitive load” on the student, thus freeing up space for concrete problem solving. The authors also highlighted the importance of thinking in analogies, reflecting on what you’ve seen before and how it fits in the model of the problem space: essentially applying problem solving strategies based on your own experience and the model you’re constructing of the problem space as you progress toward a solution.

While I was reading this paper, my mind went to two particular situations in which I was involved in coaching another firmware engineer through a problem. One was implementing a new feature in an existing system, and the other was fixing a bug in an existing system. Neither of these cases went very well: though in both cases the end result was satisfactory (the feature was implemented and the bug was fixed), both cases took more time and effort than necessary and in neither case did I get the impression that the problem and its solution were thoroughly understood by the engineer I was coaching. (My failure, not theirs.)

In the first case, I stepped in when a lot of code had already been written and another senior engineer had already been coaching the junior engineer for a while, but didn’t have time to continue. I initially assumed, wrongly as it turned out, that the problem was already understood and that the only thing the junior engineer still needed help with was to finalize some of the details and work out some of the knottier problems. Reflecting on it now, the final code looks very little like what we started with and large chunks of code have been removed, simply because they weren’t necessary to solve the problem. Taking the time to thoroughly understand the problem, without actually writing any code, would have saved a lot of time in retrospect, even though this still feels counterintuitive. It would also have led to a better understanding on the part of the junior engineer.

In the second case, I basically made the same mistake of thinking that the engineer I was coaching already had a “good enough” understanding of the problem domain: looking at the symptoms of the bug, we quickly found where the issue was and the solution was obvious, at least to me. I did have the advantage of having designed the system he was debugging, so I knew both what the expected behavior was and the history of the code. In this case, a new feature had been added to the system, and one if the state machines in the system reacted poorly to repetitive “no change” events being fed in by the new component: the state machine got stuck in a state because of those events. The problem was easily fixed by filtering out those “no change” events, but the fix failed review because the engineer I’d been helping couldn’t explain why the fix really did address the issue. Again, we had gone from diagnosis to code without validating a thorough understanding of both the problem and the solution.

In both cases, I failed to validate that the engineer I was coaching had a good understanding of the problem space. Put differently, I did not test the mental model they created to make sure the understanding of the problem, and the solution, was correct.

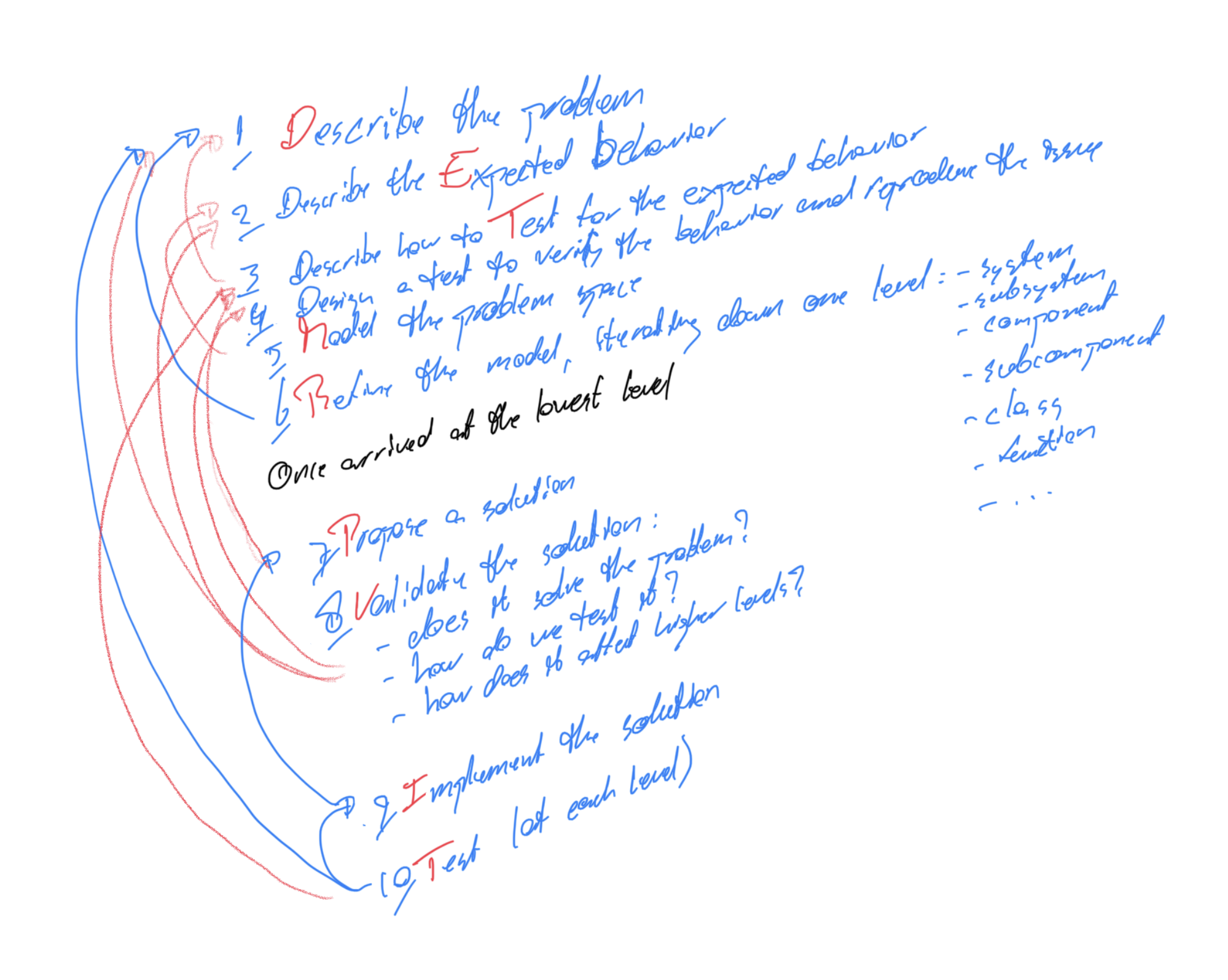

From reading the paper and these reflections, I decided to plot out my own process, inspired from the one in the paper but with a slightly more test-driven approach, to coach engineers through a problem. Unfortunately, the smallest process I could come up with was a ten-step process:

From reading the paper and these reflections, I decided to plot out my own process, inspired from the one in the paper but with a slightly more test-driven approach, to coach engineers through a problem. Unfortunately, the smallest process I could come up with was a ten-step process:

- Describe the problem

- Describe the expected behavior

- Describe how to test for the expected behavior

- Design a test to verify the behavior and reproduce the issue

- Model the problem space

- Refine the model, iterating one step down

- Propose a solution

- Validate the solution

- Implement the solution

- Test the solution

The first step is, perhaps, obvious: to reason about anything, you need to be able to describe it. This ability to reason about it is important: an accurate description of a problem is an important first step to understanding the problem. Intuitively, you know this is true: when you stub your toe, you don’t describe the problem as being the pain in your toe: rather, you describe the problem as your own clumsiness and the symptom as the pain in your toe. Similarly, “a device is not outputting a specific signal” is not a complete description of the problem either. The underlying problem in this case is that a state machine is receiving spurious events which keeps it in a specific state in which it does not generate the signal, and the way it handles those spurious events. Without a good understanding of the problem’s root cause it is hard to accurately describe the problem. So the problem starts as a pain in your toe or a signal not being generated, and you’ll start by describing it as such. You’ll refine the description later.

The second step is a step of reflection: your toe hurts, but what did you expect it to do? Obviously, in this case, you expect your toe to not hurt, in general. That’s good. Start with that, and we’ll refine it later. In the case of that state machine, the expected behavior at the first level is for the device to output a signal. This, also, we will refine later.

The third step is another step of reflection: how do we test for the expected behavior? For the painful toe, we test by asking the patient whether their toe hurts. In the case of the device, we verify the presence of the output signal.

The fourth step brings us to test-driven development: being able to show that you have solved a specific problem is both a good motivator and a good way to get closure once the problem is resolved. It provides for immediate feed-back to the developer, and provides a clear way to quality assurance. In any mature development process, validation and verification play a central role. This role started with the first step (describing the problem), and will help us through the entire process.

Designing a test also loops us back to the third step: we may need to re-think our description of how we will test the expected behavior. We may even need to refine our notion of the expected behavior at this level. Once we have a way to test for the expected behavior, we should be able to reproduce the issue at the level we’re at. If we can’t, maybe we misunderstood the problem, or maybe we should revise the design for the test.

Now, obviously, we don’t want to kick some hard angular surface to make sure our toe still hurts, but that’s not how we usually test for this kind of thing in real life: we usually take the toe and press in it a bit. A physician will do that and say “Does it hurt when I do this?” and “How about if I press here?” They’re not doing that to annoy you, or to hurt you: they’re doing it to accurately diagnose the problem.

The fifth step is to model the problem space. For the physician this means using their knowledge of human anatomy to get an idea of how bad the issue is, then perhaps prescribing an X-ray to see how bad it really is. The X-ray will be of the toe you stubbed and perhaps a good chunk of the foot. In any case your hands will be left out if it, not because it’s not part of your anatomy, but because in the model the physician had created of the problem space, the problem is not likely to be there. Similarly, in the case of our device that should be outputting a signal but isn’t the equivalent of the X-ray is to look at the device’s statistics, logs, and any other information it may provide about its functioning. To know where to look, though, you need to know about the anatomy of the device’s firmware as well: the drivers, firmware components, etc. responsible for generating the missing signal, and how that interacts with the other components.

The problem description needs to fit in the model for us to reason about it, so we may need to refine the description or adjust the model, iterating to the first and second step, and informing ourselves from those steps to gain a good understanding of the problem and its domain.

The next step is to refine the model and iterate “one step down”: from system to subsystem, from subsystem to component, from component to subcomponent, etc. all the way down to the lines of code that determine what the device should do. One step down, we start over: we describe the problem, describe the expected behavior, determine how to test for it, design a test, and create or update the model at this level of detail.

To get down to the lowest level, we may need to divide the problem into smaller problems which may individually need to be fixed in order to fix the larger problem. In some cases, solving one of the problems may solve the higher-level problem, but that is not necessarily a reason to stop: the other problems we find along the way may need fixing as well, as they may cause other visible problems.

Once we get to the lowest level, we get to where we can fix the issue. In the case of our stubbed toe it may just be giving it a little rest, but fixing the root cause may well mean buying new glasses or not texting while walking. In the case of our device it may just be a single if statement.

Now that we have a solution, we slowly start iterating back up: we validate the solution to make sure we actually fixed the problem and didn’t introduce any new ones (step 8), we implement the line(s) of code, buy the glasses, or put our phones in our pockets (step 9) and we implement and run the test we designed at step 3 (step 10). We iterate back up until we’ve validated and verified both that we have understood the problem, can explain it, and have found a solution for it.

I believe I have been using this process, or something like it, for a while now without necessarily being rigorous or concious about it: when I look at notes I took a few years back about difficult issues I was solving back then, they often resolve around how to reproduce the issues in different parts of the code, unit tests for those parts, some of which actually didn’t “break” when I thought they would. I do think, though, that making the approach more “concious” and more rigorous, I’ll be able to improve my coaching and, thus, help improve the results for the people I coach.

We’ll see soon enough.