Fundamental limitations of quantum error mitigation

People have different ways of relaxing. Some people like to watch movies, others like to listen to music, … I like to read papers, usually either about cybersecurity or quantum computing. Yesterday, I had a bit of time on my hands and decided to read on the latter: I had found an interesting paper called “Fundamental limitations of quantum error mitigation” on Arxiv, in which the authors, Ryuji Takagi, Suguru Endo, Shintaro Minagawa and Mile Gu, propose a new model for quantum error mitigation and, building on that model, find the fundamental limits.

There are a few things you need to know about quantum computing in order to understand what the Takagi et al. explain: quantum computers currently look like big, bulky devices but most of that bulkiness is actually not the quantum computer itself, but things to keep it cold, and things to let it interact with a classical computer. The reason for keeping it cold is that, at very low temperatures, you can have better control over the random noise that the universe introduces in quantum systems: particles don’t jiggle around as much when it’s really, really, cold, so they’re easier to work with.

The reason why they need to interact with classical computers is that quantum computers, by themselves, don’t really do anything useful: in order to get a useful result from a quantum computer you need to measure its output and, in order to do that, you need to let the quantum state “collapse” into a classical state. What this means, exactly, depends on your interpretation of quantum mechanics, but that’s not important right now: what you need to understand is that quantum computers are effectively coprocessors, just like the graphics processor (GPU) and the floating-point math processor (FPU) in your computer are coprocessors: neither the GPU nor the FPU do anything useful by themselves: they both need the classical “central processing unit” (CPU) to tell them what to do and get the results back out. In this sense, quantum computers are really QPUs – and that is likely what they’ll turn into once we can get them to work at room temperature and at reasonable prices.

Now, a quantum computer is subject to noise in a way that a classical computer is not: when a classical computer’s memory bit gets hit by a cosmic ray, it can flip, but classical error correcting codes (such as the good ol’ Hamming code) can detect and correct for that. This is why computers that are subject to a lot of cosmic rays (e.g. because they’re in space) or for which it is very critical that bits don’t flip without it being corrected either have very old hardware (which is less sensitive to such cosmic rays because their components are bigger, needing more than a stray proton to flip a bit) or employ error correcting codes in their hardware to compensate. Quantum computers get hit by cosmic rays just as classical computers do, but they’re also sensitive to normal light, heat, and just the basic randomness of the universe. Add to that the fact that if anything disturbs them, the effects are far more unpredictable than just a bit flipping (because there’s more information in a qubit than there is in a classical bit, see my post on the subject from two years ago) and we start needing error correction all the time.

One more thing you need to know to understand this paper is that quantum computers implement quantum circuits, which consist of quantum gates. These gates take a quantum state as input, which is usually represented by a Greek letter such as $\Psi$ or $\Phi$. Quantum circuits transform an input state into some other state, and can in theory always to the inverse: quantum circuits, unlike classical circuits, can be run backwards so to speak. This means that a quantum circuit is a transform in the strictest possible sense of the word: if you can divise a quantum circuit that transforms $\Psi$ into $\Phi$, then you have also divised a circuit that transforms $\Phi$ into $\Psi$. This may seem trivial, but the same is not true for classical circuits: if I have a circuit that adds $a$ to $b$ (i.e. $a + b = c$) I and up with a value $c$ that tells me next to nothing about $a$ and $b$ (except that their sum is $c$). Quantum circuits cannot do this, because they cannot “throw information away”.

Errors therefore come from three places:

- Design errors in the quantum circuits (i.e. bugs), which are considered “bias” in this paper and otherwise remain out of scope

- Noise injected into the circuit, which is both unpredictible (i.e. random) and unmeasurable

- The hardware the quantum circuit runs on, which like any hardware doesn’t always do what you want because the universe isn’t perfect and doesn’t allow for perfection to exist within it

Discounting the first source of errors, the sources of errors can then be seen as either errors being injected into the quantum channel as originally designed, and as a an error channel that is applied to the same inputs. In effect, they don’t explain it like this, but you could see the error channel as a transform applied to the quantum channel that’s being implemented itself. Say you have a function $F$ that applies a transform to a quantum state $\Psi$ such that $F(\Psi) \rightarrow \Phi$, the error channel $\epsilon$ effectively modifies the function $F$ such that in stead of $F(\Psi) \rightarrow \Phi$ you get $\epsilon_F(\Psi) \rightarrow \Phi’$, in which $\Phi’$ is some “distorted” version of $\Phi$. Now add noise, which essentially transforms $\Psi$ into some $\nu(\Psi)$, what you end up getting is $\epsilon_F(\nu(\Psi)) \rightarrow \phi$.

Quantum error correction tries two things: it tries to minimize, or undo, the noise transform $\nu(\Psi)$ by either averaging it out using classical statistical analysis, or canceling it out using a quantum circuit; and it tries to minimize, or undo, the error channel’s transform of the original circuit using pretty much the same approaches. Canceling out the error channel using a quantum circuit is only feasible if the error channel itself is predictable, or at least understood. With noise, it’s even harder.

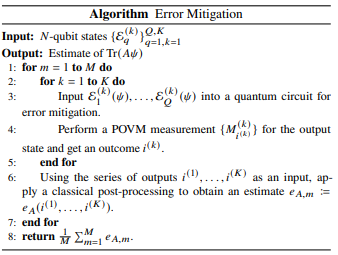

The way quantum circuits apply error correction boils down to three steps:

The way quantum circuits apply error correction boils down to three steps:

- Run the quantum experiment $K$ times in parallel, then apply a quantum circuit to the outcome of those parallel runs’ outcomes to get the noise to cancel itself out

- Run the quantum experiment $M$ times in a row, then apply a classical analysis to the measured outcomes to average out the errors

- Do all this with $Q$ different, independent inputs

The figure to the right was taken from the paper to illustrate.

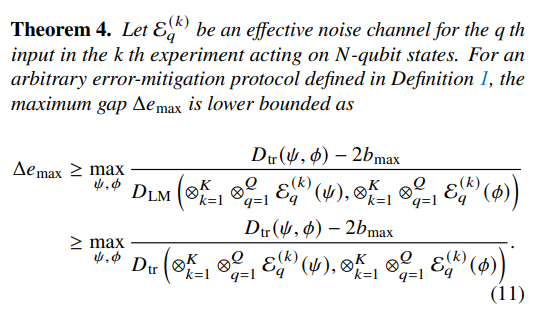

They go on to define $\Delta e_{max}$, which represents the maximum expected difference between the minimum and maximum value that can come out of a measurement in an $N$-qubit system, and that’s where things get interesting: they show that by optimizing the values for $Q$, $K$ and $M$, you can optimize to minimize $\Delta e_{max}$ thus optimizing for accuracy.

With that definition, and quite a bit of math, Takagi et al. come up with a theorem that I find particularly beautiful, shown in the figure to the right (note that in that figure the authors use $\Psi$ and $\Phi$ as two different input states, not as input and output resp. as I did above).

With that definition, and quite a bit of math, Takagi et al. come up with a theorem that I find particularly beautiful, shown in the figure to the right (note that in that figure the authors use $\Psi$ and $\Phi$ as two different input states, not as input and output resp. as I did above).

They then go ahead and apply their new model to different types of existing error correction and mitigation schemes: probablistic error cancellation, Richardson extrapolation, and Virtual distillation. This is where they run into a wee bit of trouble, when they consider stacked quantum circuits that have interlaced error mitigation strategies within the overall circuit. In stead of formulating their model to be composible (which it can be: it is essentially a classical measurement function so while it can’t be composed into a quantum circuit without collapsing any intermediate quantum states, it can be composed as a classical function), they fudge the issue by declaring that “when the circuit solely consists of Clifford gates and noise is a probabilistic Pauli channel, we can see that this strategy, which applies on-site mitigation operations, still falls into our framework, allowing us to apply the general bounds”. It would have been interesting to build on the framework and generalize it to include probablistic error cancellation in a layered circuit.

Regardless, the framework as defined by Tagaki et al. could be used to determine, while running a quantum circuit and estimating the maximum bias, you can optimize the number of times you run the circuit on the same inputs and this optimize the accuracy of the output. With this in mind, a quantum computer (or a quantum coprocessors, rather), with help from a classical CPU, could be made more tolerant to noise and to errors as control of the quantum computer could be dynamically adjusted to optimize the output. This opens up the possibility to using this new understanding of the fundamental limits of quantum error mitigation to design quantum computers that are “good enough” when it comes to them producing erroneous output due to noise and hardware errors, leveraging dynamic error correction to mitigate for poorer quality. Essentially, this is a (small, perhaps tiny) step toward a desktop quantum coprocessor.

OK, this last paragraph is admittedly me being more optimistic than the paper would lead me to be but that is, after all, what relaxing is for.