Eliminating waste as a way to optimize

I recently had a chance to work on an implementation of an Arachnida-based web server that had started using a lot of memory as new features were being added.

Arachnida itself is pretty lean and comes with a number of tools to help build web services in industrial devices, but it is not an “app in a box”: some assembly is required and you have to make some of the parts yourself.

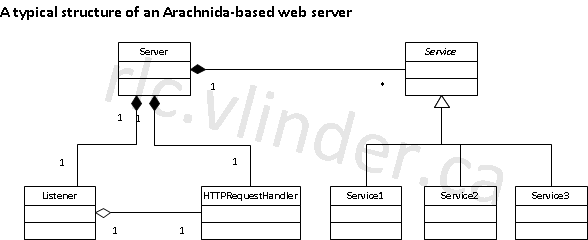

In most cases, the resulting web server looks a lot like one of the examples: there’s a Server class that contains the Listener instance, HTTPRequestHandler and a bunch of objects that implement services using a Service interface. Each service implements a part of the web application and is responsible for responding to its requests. To dispatch between different services, usually, some part of the request URI is used.

This scheme works very well: it allows you to separate the responsibilities of each service neatly into classes. It sometimes comes with a bit of a trade-off, though: you often end up duplicating information in different services, unless you go ahead and implement a full-fledged MVP, which most people don’t.

The code I was looking at used the standard std::string in many places and hooked into APIs that I couldn’t change for the purposes of this optimization, and used std::strings as well as raw char const* pointers. Arachnida comes with Acari, and uses Acari extensively itself – which helps to keep it lean. Acari comes with a very agressively optimized string class for this kind of situation, where strings get copied around a lot (which, in parsers, is pretty common). The best option I had, therefore, was to find out, for each string, which copy I should keep and whether I could count on its longevity. Those that I could count on for staying alive would then be referenced by instances of a non-copying String class from Acari, or Vlinder::Lite::String (an even lighter version of Acari’s String class) in some places.

This took care of a large part of the problem, but not all of it, so I had to dig a little deeper. Here’s some of the tricks I applied:

Instrumenting the code:

At key places (start of main, before and after the initialization of singletons, before and after the creation of several key objects, before and after reading configuration, etc. etc.) write a debug trace indicating how much memory is being used.

This is basically a poor man’s profiler, but it allows you to easily find chunks of code that use inordinate amounts of memory. Sometimes, though, the system may play tricks on you when the system’s allocator tries to help out by reserving more memory for your application than you need to – so you need to look out for false positives.

Go for the low-hanging fruit: When memory usage becomes problematic enough to devote several hours to it, there’s likely to be a lot of low-hanging fruit – things that take a lot of memory and shouldn’t. Determine a threshold (e.g. 1 meg) and don’t bother with anything below it, at least until you’ve run out of candidates at or above that threshold.

Reduce caching: the server used what effectively came down to a mirror of a cache internally, while it had access to the cache itself – removing the cache’s mirror removed a few megabytes of memory footprint.

RAII:

Using RAII consistently greatly reduces your chances of having memory leaks – or even of letting objects stay alive longer than necessary. Replacing calls to malloc with std::vector instances ended up shaving another megabyte off the application’s footprint.

Find big static variables using objdump or dumpbin: Both binutils and the Microsoft SDK come with a tool to dump the headers of generated binary files. You can use those to find big static variables and, then, use the code to evaluate whether those variables really need to be that big. On the target platform, we could reduce the footprint of static variables by over 80% using this approach.

Conclusion

This particular instance of an Arachnida server was unusual in that the smallest of the family of devices it runs on was still rather large (128 MB of working memory) – but that’s becoming more and more common. While Arachnida itself was not part of the problem, one of its component parts was part of the solution and this gave me a chance to work with one of its instances for the first time in a rather long time (I usually only get to answer a few questions or implement the occasional feature request, but I don’t get to play with the end-product’s code much, so I mostly let those questions guide where development should go next). So suffice it to say I’m happy to know my web server is being put to good use in non-trivial projects – and people are getting their money’s worth (which isn’t surprising: they wouldn’t come back otherwise).