A different take on the "optimize by puzzle" problem

I explained the problem I presented in my previous post to my wife overt dinner yesterday. She’s a professor at law and a very intelligent person, but has no notion of set theory, graph theory, or algorithms. I’m sure many of my colleagues run into similar problems, so I thought I’d share the analogies I used to explain the problem, and the solution. I didn’t get to explaining how to arrive at computational complexity, though.

Say you have a class full of third-grade children. Their instructions are simple:

- They cannot tell you their own names – if you ask, they have permission to kick you in the shins.

- Each child has their hands on the shoulder of zero one or two other children.

- All the children are facing in the same direction.

- Only one child has no hands on their shoulder.

- You can ask each child the names of the children whose shoulders they have their hands on, but they will only tell you once – ask again, they’ll kick you in the shins – and you have to address them by their names.

You are told the name of one child. How do you get the names of all the children without getting kicked in the shins and which child do you have to get the name of?

Obviously, the child whose name you have to know in advance is the one who doesn’t have any hands on their shoulders. From there on, you need to keep track of the kids whose names you know but haven’t asked yet (the to_check set) the kids whose names you know and have addresses (the checked set). At the end, you’ll have checked everyone, so you group of kids whose names you know but having asked yet is empty.

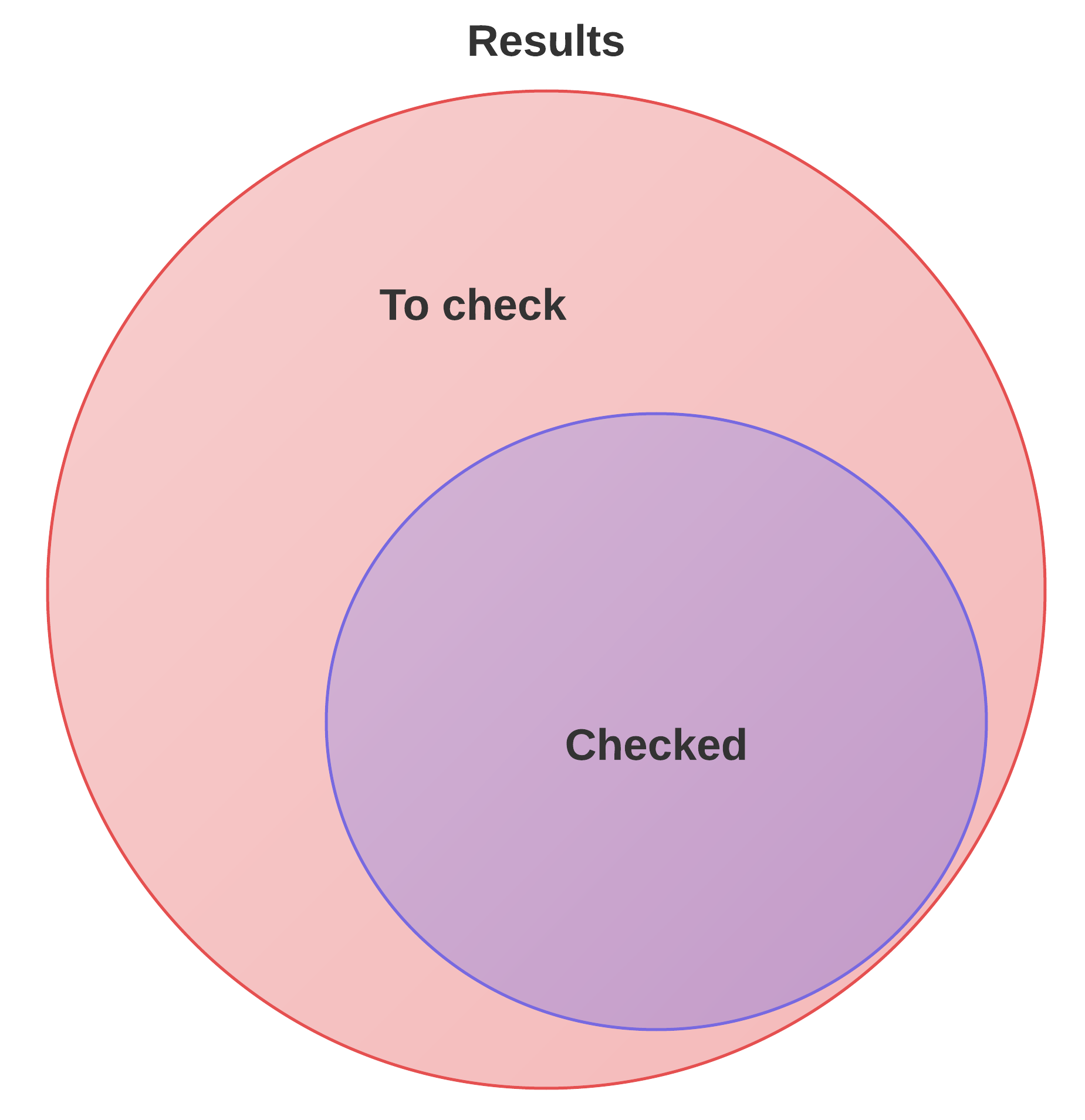

The third set (the results set) really only exists to make getting the “right” part of the set. As shown in the Venn chart below, the set of kids remaining to be checked is the difference between the result set and the (entirely overlapping) set of kids we checked with.

And that’s exactly what the algorithm does.