Flawed ways of working: centrally managed version control

Imagine, just for a moment (it would be painful to do this longer than just a moment) that Linus, when he decided to leave BitKeeper behind, switched to Subversion in stead of developing Git and that for any commit into the master branch of that repository, you’d need his approval. While you’re imagining that, just a few microseconds more, imagine he stuck to his guns.

Either Linux would no longer exist or Linus would have been declared mad, and Linux would have moved on without him.

Centrally managed version control systems are fundamentally flawed and impede productivity. Any project with more than a handful of developers/programmers using a centrally managed version control system will either lose control over the quality of the product, or bring productivity to a grinding halt.

There are several popular centrally managed SCMs Out There: Microsoft has TFS, many open source and commercial projects use Subversion – some people even still use CVS1. I’ve personally worked with TFS, SVN, CVS and MKS – I’ve even used RCS, though that is arguably the first distributed version manager2.

CVS is, of course, fundamentally flawed because it not only doesn’t guarantee that what you get out is what you put in, but it practically guarantees the reverse: what you put in will be modified in various subtle and not-so-subtle ways, so you will never see it again. So we won’t discuss CVS any further, nor will we discuss RCS, which underpins CVS and has the same fundamental flaw w.r.t. what’s put in and what you get out. The same goes for MKS, which is basically CVS with a few extra flaws3.

I will argue, however, that all centrally managed version control systems are fundamentally flawed: they impede cooperative development, they diminish productivity and they introduce unnecessary bottlenecks in the development process – even if there is only one “canonical” version of the software.

The basic premise of a centrally managed version control system is that only one version of the software is “real”. That version is often called the “trunk”, “current” or some other such term indicating that the software in question is the mother of all (“official”) versions. I have no problem with that premise: there is only one “canonical” version of Arachnida, µpool2 and any of the other Vlinder Software products, and that version is whatever version I have personally approved every single commit (or change set) of. The centrally-managed model fails when any change to the code only becomes available to other developers after they are integrated into the master version.

For example: when testing an application that represents the user-space part of a functionality I’ve designed and implemented for an industrial embedded device, I found a design flaw in a different part of the device’s software that made my test fail. I analyzed the problem, came up with a solution, and discussed it with the company’s lead analyst. We agreed on the solution and I created the branch (in TFS) to fix the problem, fixed it and had it peer-reviewed. That part of the process took about an hour, a significant part of which was creating the branch in TFS (which took about five minutes – so 10% of the total time to fix the bug) – another significant part was the administrative overhead of creating the work item etc., but I have no problem with that part of the procedure. The bug, which had to be fixed in a separate branch due to the “one item one branch” mantra, is now waiting for approval to be checked into the trunk – and has been for several hours.

Clearly, something is wrong with this picture:

- fixing a bug on which the test results of an important feature depends needs to be done in a separate branch so it remains trackable: each work item corresponds to a single commit in the trunk, so it’s easy to find the change set that implements a specific fix;

- every feature or bugfix must be developed in its own branch, so check-ins into the trunk really only touch one thing (probably the most-broken rule in this type of practice)

- every development branch is created directly from the trunk (because it is difficult to track development otherwise).

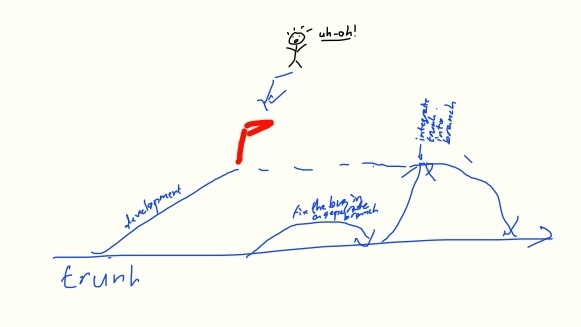

In case it’s not clear what is wrong with this picture: let me make a sketch:

The important bit of this sketch is the arrow on the right, that says “integrate trunk back into branch” and the dashed line from the discovery of the bug to that “forward integration”: from the point where the bug is discovered until the point that the development branch is re-synchronized with the now-fixed trunk, development in the branch is at a stand-still.

In software engineering terms, this means that inter-dependent development branches are blocked by their relative integrations into the trunk.

Now, you might say that this doesn’t mean the centrally managed source control is at fault but rather, the procedures using that system are flawed, and you would be partly right. However, this approach to managing the trunk is very common and almost inherent to the way centrally managed source configuration management works: these are the “good practices” of the system.

But even if we say it’s the procedures that are faulty fixing the design flaw in this case – and in many cases like it – could have been done in the development branch of the feature I was testing. That branch contains many, many changes to the product, however, and this particular fix will have to go into the trunk, and future releases of the product, well before I’ve finished testing the new feature – let alone waiting for approval to integrate it into the product after peer reviews. Centrally managed source control, whether it be Subversion, TFS or some other system based on its principles, have a hard time “cherry-picking” a single changeset and integrating it into another branch. For a long time, Subversion had no real support for merging at all: support for merge tracking was introduced in version 1.5. This is understandable, as Subversion doesn’t actually know what a branch is. Let me quote the Subversion book to back that up: “You should remember two important lessons from [the section about branches]. First, Subversion has no internal concept of a branch—it knows only how to make copies”. What subversion really does is copy files around and keep track of the history of the whole repository – branches and all. This is OK, except when the user does something stupid, which is what users inevitably do. “Something stupid” could be modifying the trunk and a “branch” in a single changeset, for example, or more generally modifying more than one branch is a single changeset. It may not seem stupid at the time: it may even seem like a great idea, but it messes up the way the system works. With architectures like these, cherry-picking becomes very difficult because the system not only has to figure out what changes you want to pick, but it has to invent a notion of a “branch” on the fly. It appears to do this by keeping track of what it considers a “special” part of the history of each file using a “merge info” property which even the subversion book describes as “very complex”. This design gets into trouble fairly quickly when you try to keep your branch synchronized with the trunk and cherry-pick changesets from an otherwise unrelated branch.

TFS has a design very similar to Subversion – at least on the surface. Fact is that TFS is closed-source and Microsoft is fairly tight-lipped about the design of its internals. TFS has a similar lack of support for cherry-picking, although it does allow something fairly close by using the command-line.

The point is, though, that centrally-managed source control systems just aren’t designed for collaboration that doesn’t either have the collaborators working in the same branch (which requires careful coordination and often requires the software architecture to be amenable to that kind of cooperation) or code being duplicated among branches. Most distributed versioning systems have no such problem.

Now, let’s look at the alternative. Like I said, I don’t have any problem with a single version of the software being dubbed the “master”, “canonical”, or “trunk” branch which is where all “official” versions come from, but with a distributed versioning system such as Git, that doesn’t have to mean that every fix has to go through that branch to be useful to others on the team and keep track of its history. In the situation I described above, there are two alternative stories that could have happened: either I fixed the bug in my branch, had the fix peer-reviewed and got permission to merge the fix, and only the fix, into the trunk, which would have meant a cherry-pick from my branch into the trunk by some-one who has the power to push into the trunk (which could very well be me, but wouldn’t necessarily be me), or the bug got fixed in a separate branch, and cherry-picked into mine without having to wait for approval to go through the trunk.

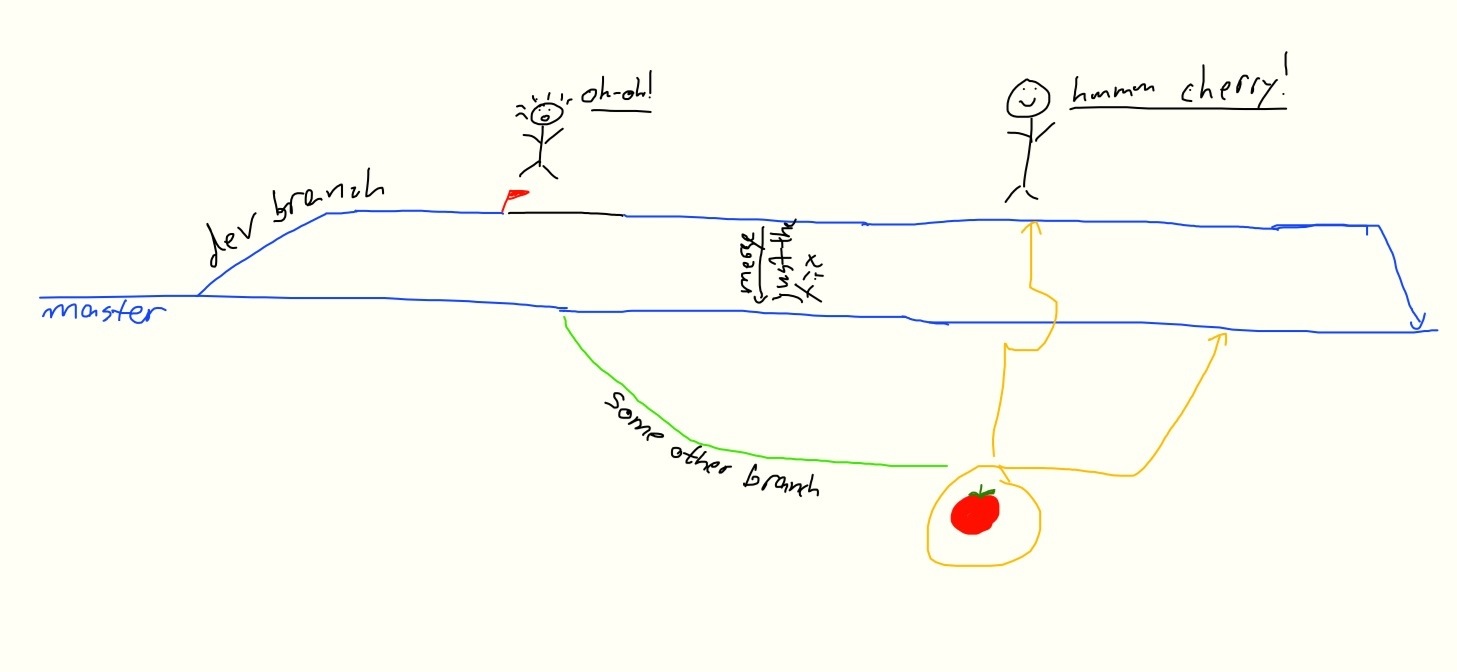

Here’s another sketch with those two scenarios:

The thing you should understand is that neither of these two scenarios would require waiting for approval to do anything – which entails a costly context switch to get the developer to work on something else or manually merging the fix into the development branch, which is also costly and can lead to conflicts down the road.

There is, of course, a counter-argument: if there’s a bug in the fix, that bug will affect more people more quickly because the fix will have been merged into a variety of branches before ever being reviewed and approved. That is true, but the fix for the bug introduced by the fix is propagated in much the same way and will end up in the trunk once the approval process has gone through. Once fixed, it stays fixed, even if other branches that don’t contain the fix are merged into the trunk at a later date.

I’ve helped migrate a team from MKS to CVS, which was a huge step forward. I’ve migrated a team from CVS to Git (I was in charge of that team) which was a giant leap forward. In both cases, some ways of working had to change. The first team was far bigger than the second, but the second team had a far steeper learning curve to hit. Once they got up the learning curve, however, none of them wanted to turn back – they turned sideways a bit, swapping Git for Mercurial because it had better support for Windows at the time, but not back.

-

No, really, I mean it! ↩

-

Again, I mean it, really! ↩

-

The place I used MKS at made significant progress when they moved to CVS, partly due to a push in that direction on my part – yes, really, I actually influenced a whole team of developers to start using CVS. In my defense, this was before Git existed, before Subversion was anywhere near being stable, and CVS really is a lot less bad than MKS.. ↩