Developer's Guidelines & High-Quality Software

Yesterday, I was asked what I saw as the most important factors to ensure the development of quality software. What I cited was good design, good implementation following good standards, and good testing. On the testing end, I have a rule-of-thumb that says that at least 85% of the code should be covered with unit tests - and for the parts that aren’t there should be a clear reason/rationale for it not being covered. Unit tests aren’t enough, however: you also need functional tests, regression tests, etc. IMO, pre-production testing should be an important focus for any software-centric development team. But the subject of this post isn’t testing - it’s developer’s guidelines.

Dr Dobb’s Survey

A (more-or-less) recent survey, published on Dr Dobb’s had some interesting things to say about using developer’s guidelines. Here’s some excerpts from the article, each of which I will comment on:

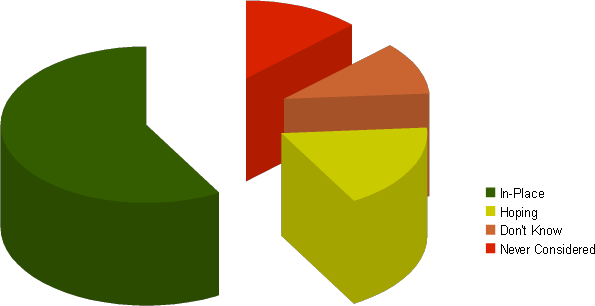

59% of respondents indicated that their organization has enterprise-wide coding conventions. (...) Of the remaining 41% of respondents, the survey found that 32% had not considered enterprise conventions and that 44% hoped to put them in place one day (everyone else wasn't sure if they had coding conventions at all).

Let’s take a look at what that means:

while a small majority has standards in place, an appalling number of businesses and developer teams still don’t - and some don’t know, which means that if there are any, they are not being followed. Let’s take another quote (from the same parahraph):

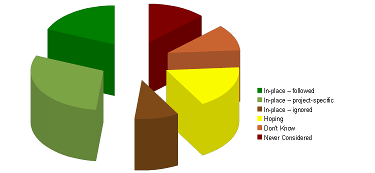

of the respondents who indicated that they have enterprise-level coding guidelines, 17% indicated that developers were more likely to follow their own programming conventions anyway, 51% of them indicated that it was more likely for developers to follow project-specific conventions, and the remaining 32% to actually follow the enterprise conventions

Let’s take a look at what that means:

now, the part of developers that actually follow enterprise-level standards is reduced to about 18% and 52% is not using any standards (but some of those are hoping that standards might come one day). On the bright side, at least about two-thirds of developers seem to understand the importance of shared standards and are either applying them, applying them but badly managed, or hoping they’ll come one day.

I see two major problems in this: first, I see a lack of enterprise-level comprehension of the importance of shared standards, meaning that if there are different development teams, those teams are likely to not have the same standards. In “low” times, this may not be a problem, but it reduces the mobility of your programmers between your teams (i.e. if one team needs help, a programmer from another team will have more trouble integrating with the team to help them out). This also means that higher levels of management won’t necessarily understand the reason for being for any standards that do exist, and will pressure development teams to “just hurry up”, which, in the long run, is a counter-productive pressure.

Second, I see a lack of programmer-level comprehension of the importance of shared standards. This is evident from the results where even in those businesses that do have enterprise-wide standards, 17% of programmers will follow “their own standards” anyway. This could of course indicate a lack of quality in those enterprise-level standards, but if that were the case, the programmers would follow a superset of the standard, not a completely different one. Still, there is hope in this category: 67% of programmers, which is two-thirds, seem to understand the importance of standards, although the results don’t say whether they understand the importance of enterprise-level standards.

Advantages of Enterprise-Level Standards

Aside from inter-team mobility for your programmers, there are quite a few business advantages to having enterprise-wide coding standards:

- reduced time-to-market

new features are developed faster if they are to be integrated with software that already follows a standard: it makes the software to b integrated with more predictable, meaning the analysts and programmers spend less time trying to figure out how to integrate the new feature; - less service costs

many businesses try to make money selling service contracts in the hope that the customer won’t use them, but find out the customer does use them, and start losing money as a result - high-quality software leads to less service calls, enterprise-level standards lead to high-quality software; - higher quality

implementing enterprise-level standards means you can verify and validate your software against those standards and catch problems early in the product life-cycle, meaning the quality of the end product is higher; - lean manufacturing

one of the “seven wastes” is Defects, of which you can reduce the impact by catching them early, and which you can eliminate using good standards and good manufacturing practices. One important thing to take into account, however, is the quality of your standards: a low-quality standard will have little or no positive impact on the quality of the code, and may even have a negative impact! For example, a standard that says that “at least 50% of the source code file’s text should be comments” is appealing to a lot of people, including a lot of programmers, but it really depends on what you put in your comments whether it’s of any use: comments aren’t verified by the compiler, so they mey lie about the code. Documenting the code’s history in the comments is simple nonsense: there are version control (SCM) systems for that.

Developer’s Guideline Quality

What does it take for a developer’s guideline to be a good developer’s guideline? What are the ingredients of a good developer’s guideline? Well, before I say anything about that, I should quote Andrei Alexandrescu and Herb Sutter and say: “don’t sweat the small stuff”. Don’t try to tell people where to put their semicolons.

Things you do need to put in your guidelines are things that will help your programmers create secure code, code that performs well, code that is thread-safe (if applicable) and code that is maintainable, stable (both in terms of API and in terms of mean time between failures) and scalable. In my opinion, these latter three should really be the focus of any developer’s guideline: the rest will follow.

The danger of having a bad developer’s guide are legion: you will lose productivity, developer buy-in (which is important to keep them on your team) and, in the long run, any kind of quality. You’d probably be better off without a developer’s guideline than with a bad one.

Maintainable

From the business point of view, you need your software to be maintainable: you need to reduce your time-to-market and you need to reduce the time between a bug being found and the fix being shipped. There are diverse ways to improve the maintainability of your code through a shared coding standard/developer’s guide. One of them is to have a shared style for all of the code, so five years from now, your programmers can check out that long-forgotten module in which you’ve just decided you have to add a new feature, open up the code, understand it at a glance, and add that feature.

Another part of maintainability is documentation: programmers usually neither like reading nor writing documentation, so you need to keep your documentation requirements to a minimum in order for your programmers to actually use it (or create it, though that can be enforced); but you also need your documentation to be sufficiently complete so a new programmer can understand how the code is set up without actually having to read all of the code. This minimal but complete approach (which applies to other things than documentation as well) really allows you to augment the quality of your documentation and the maintainability of your code, and guidelines pertaining this should be part of your developer’s guidelines.

Minimal but complete is also the mantra for API design: in order for a software module to be maintainable, it has to be encapsulated as well as possible, so the API doesn’t tell the user how the functions are provided, but just tells him what functions are provided and what the pre- and postconditions of those functions are. Guidelines pertaining API design should therefore also be part of your developer’s guidelines.

Stable

Stability really comes in two kinds: the “I won’t need to change the client code for this modification” kind and the “I can trust this application with my data, with my process, with my life” kind (and no, the last one is not an exaggeration: just think of all the software in an airplane). These two types of stability are really very different: one is a productivity concern whereas the other is a value concern.

API Stability

API stability reduces time-to-market: it means that adding a new feature to an existing module (library, service or otherwise) may add something to the API of that module, but won’t break anything that already uses the module, like removing a feature from the module would. This means that your APIs have to be well-designed, which means that even in agile development teams there is some thinking ahead to be done: even if according to the specific methodology you use you’re supposed to concentrate on only one user story, use-case or what-have-you at a time, you should still take those other cases into account when designing your API.

You should not, however, push that too far: you should not go into a whole ramble of what-ifs and yes-buts. On the contrary, you should take a very conservative approach to API design: decide what functionality your API will represent to the system (in which functionality can be in the service-sense, in the object-sense or in whatever sense best applies to your context) and limit your API to that functionality. For example, if you need something to interact with PLCs, you don’t normally need functionalities to parse XML in the same API. You might use XML for something behind the scenes, but that’s not what your API is about.

Mean Time Between Failures

The other tangent of stability is the mean time between failures. This is where security concerns are involved, but it is also where you need to look for resource leaks, and bugs in general. The most common MTBF-related problems, in my experience, are also very easy to get rid of: they are resource leaks (which are very easy to avoid by applying a very simple coding standard); deadlocks which are provably avoidable by correctly ordering the acquisition of your locks; “access violations” (this is the Windows term for “segmentation fault”, but it basically means accessing a resource you haven’t allocated (anymore) or dereferencing a pointer that doesn’t point anywhere valid), which is also very easy to avoid, either by using smart (or unsmart) pointers, or by making sure pointers that don’t point anywhere are nulled and checking before accessing; and unhandled exceptions and other exception-safety issues, which can be handled by standards as well.

The one type of error that is very hard to catch just by applying standards, but which it is possible to catch using certain static analysis tools, is the race condition: they are hard to catch at run-time, hard to find when reading the code and hard to diagnose when they pop up - there are some things guides can’t fix.

Scalable

Scalability is the capacity of the system to accept more input and/or generate more output without significantly changing the system, both in throughput and in format. From a software perspective, this means (among other things) that the software should not be tied to the specific electronics platform it was originally developed for: it should be portable to the extent applicable to the software in question (e.g. it should not be limited to using a single core of the CPU by design if it is at all possible for it to parallelize certain parts of its logic, but for a firmware, it may very well be acceptable for at least part of the software to have to be re-written to put it on another platform).

This often means that your architecture needs to take your scalability requirements into account, but at the implementation-level, there are also scalability requirements that should not be lost from sight. Developer’s guidelines can help ascertain that the software is portable, is not limited to specific communications protocols, file formats, etc.

Other Concerns For Guideline Quality

For the guideline itself, there are three things that can greatly improve its quality: presentation, structure and enforcement.

A guideline should be more than just a list of rules and regulations and should definitely not be a law book: it should be easily accessible, preferably something you could present as a wiki, and you should allow the programmers to comment, be able to give a rationale for most (if not all) of the rules you enforce.

The structure of the guideline should be clear: if a new programmer on the team asks himself “how should I do this?” he should be able to find the answer easily, not have to go through all of the rules to find his answer. Again, presenting the guidelines in a wiki, which usually means you can search it, is a good thing here, but the structure itself should lend itself for quick searches as well - especially for printed copies.

You should also enforce those rules that need enforcing, work on peer reviews, static analysis, etc. to make sure the rules are being followed. Guidelines that aren’t followed eventually become inapplicable to the code, thus reducing the quality of the guideline as well as of the code.