Bayes' theorem in non-functional requirements analysis -- an example

I am not a mathematician, but I do like Bayes’ theorem for non-functional requirements analysis – and I’d like to present an example of its application1.

Recently, a question was brought to the DNP technical committee about the application of a part of section 13 of IEEE Standard 1815-2012 (the standard that defines DNP). Section 13 explains how to use DNP over TCP/IP, as it was originally designed to be used over serial links. It basically says “pretend it’s a serial link”, and “here’s how you do TCP networking”.

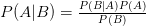

The use-case in question involved a master device talking to several oustation devices over a single TCP connection. The TCP connection in question really connected to a port server, which transformed the TCP connection into several serial connections.

The standard tells the master and the outstation to periodically check whether the link is still alive, and to close the TCP connection if it isn’t. This works fairly well in the specific (but most popular) case where the master connects to a single outstation using a TCP connection. I.e. in that case (here comes Bayes’ theorem):

I.e. the probability that the TCP connection is broken given that the DNP link is broken is equal to the probability that the DNP link is broken given that the TCP connection is broken, times the probability that the TCP connection is broken (at any time), divided by the probability that the DNP connection is broken (at any time). As the probability that the DNP link is broken given that the TCP connection is broken is 1 (the DNP link is wholly dependent on the TCP connection), this is really the probability that the TCP connection is broken divided by the probability that the DNP link is broken. The probability that a DNP link breaks, given a production-quality stack, should be very low, and about equal to (but strictly higher than) the probability that the TCP connection breaks, so one may safely assume that if the DNP link is broken, the TCP connection is also broken2.

For the remainder of this article, we will assume that the devices on the other end of the TCP connection are more much likely to fail than the TCP connection itself. While this was not our assumption before, and is not an assumption I would expect the authors of the standard to have, applying this assumption to a case where there is only one device at the other end has very little effect on availability, as closing the TCP connection does not render any other devices unavailable, while it a disconnect/reconnect may fix the problem – the near-zero negative effects of a false positive far outweigh the positive effect in case it’s not a false positive: even if you have a 90% chance that a disconnect/reconnect doesn’t work, it can’t hurt. This is obviously not the case in our use-case, where such a false-positive rate greatly diminishes the availability of other devices on the same connection. I.e., we will assume five-nines (99.999%) uptime for the TCP connection and four-nines (99.99%) uptime for the DNP3 devices.

The use-case in the standard – one master, one outstation, one connection – is the use-case the member came up with, which involved one TCP connection, but DNP links – the other DNP links were still working, for as far as we could tell.

The probability that all DNP links go awry at the same time is very small indeed

( – i.e. the probability that the TCP connection is down plus the probability that all DNP links are down while the TCP connection is still alive – to be precise), but still strictly greater than

, so our equation now becomes:

but the probability that the TCP connection is broken given that only one DNP link is broken is very small, namely:

Note: it is impossible for a DNP link that is wholly dependent on the TCP connection to be available while the TCP connection is not. Hence, as long as one DNP link is still available, the TCP connection is necessarily still alive. This means that deciding to break the TCP connection on the assumption that it was already broken while some DNP links are still communicating has the clear effect of reducing availability (the opposite of the intent).

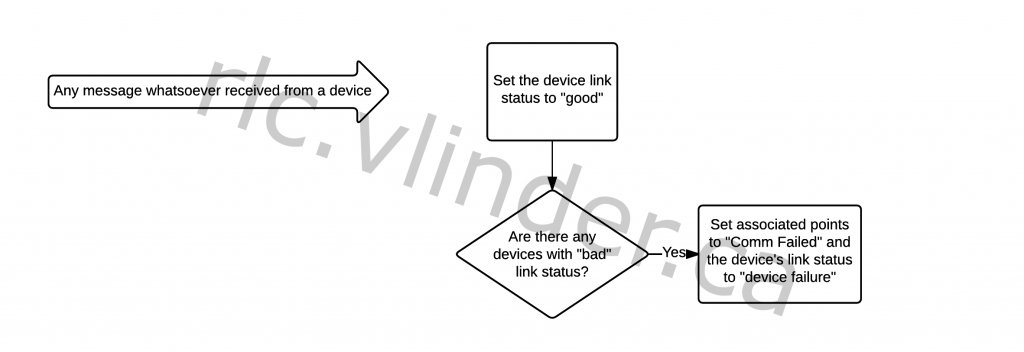

So, if you don’t decide to cut the TCP connection as soon as you see a DNP link going down, when do you decide to cut the connection?

The issue with this question is that, while as long as there is only one link for any connection we can think in terms of “good” and “bad” links, as soon as we have more than one link we have to add the notion of an “unknown” state and a “device failure” state.

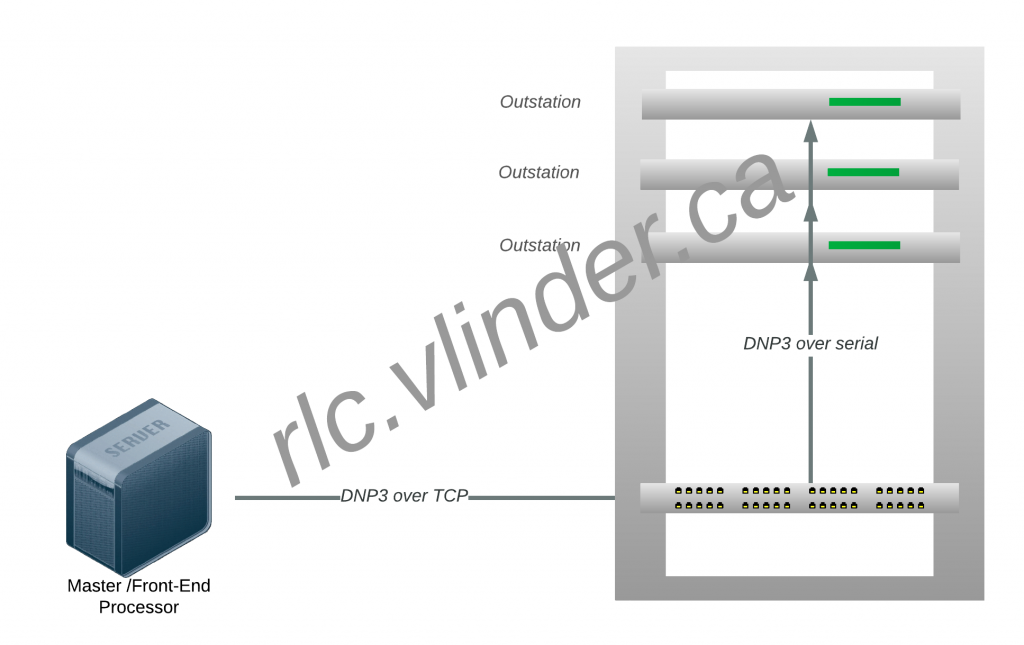

If any message is received from any device whatsoever, it is clear that the TCP connection is still alive and that any device link that is down at the moment is due to a device failure.

That means that in any assessment of the likely state of the TCP connection, any devices that were previously marked as having a “bad” link status are no longer relevant: they most likely failed because of a device failure.

So, when a link status request times out, we really only know that the link status of the device for which it timed out is “bad”, and that we can no longer assume that the devices for which it was “good”, it still is “good”. This is the moment where we should assess whether the TCP connection is at fault – in which case it should be closed – or whether something else is wrong. What we need to know is .

As shown above, 3. Now, if we have five-nines uptime for TCP and our-nines uptime for DNP3,

– hence the “90% chance that a disconnect/reconnect doesn’t work” I mentioned earlier.

If, however, we find that there are two DNP links that are down, . This is somewhat more difficult to calculate correctly, because while it would be tempting to say that

, that is clearly not accurate as we know, due to the complete dependency of the DNP link on the TCP connection, that

, so

is really

, which, in our case, assuming five-nines for TCP and four-nines for the DNP3 link, means

.

So, while with only one system’s link down the probability of the TCP connection being the problem is only 10%, when the second link goes down, absent knowledge of the link being OK between the first and second down, the probability of the TCP connection being the problem shoots up to nearly 100%. This means that there is no need, at that point, to probe the other devices on the connection.

Note that this is regardless if how many devices there are on the other end of the connection: as soon as there are two devices that have failed to respond to a link status request and no devices have communicated between those two failures, it is almost certain that the TCP connection is down.

-

I was actually going to give a theoretical example of availability requirements, but then a real example popped up… ↩

-

I should note that this implies that

is very small indeed which, given that we’re talking about link status requests, which are implemented in the link layer and in most implementations don’t require involvement of much more than that, is a fairly safe assumpion. ↩

-

Because

↩