Ranges

The concept of a range is one of the fundamental concepts in the design of the STL and of the C++ programming language. In this installment, we will take a close look at what a range is, and we will take a look at some parts of the design of the STL. This will help you to understand the lines of code I skipped over when we looked at the code in the previous installment. In the next installment, we will look at that code again.

This installment is heavily based on a tutorial presentation on ranges in the STL, of which the slides are included.

In this installment, we will go through the presentation on iterators, ranges, containers and standard algorithms. We will see what an iterator is, what a range is, what kind of iterators there are, what kind of containers there are and what kind of algorithms there are. By the end of the presentation – and of this installment – you will understand why certain algorithms need certain types of iterators, and why iterator categories are important.

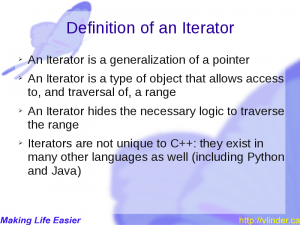

Iterators are a generalization of pointers. That means that every pointer is an iterator - though not every iterator is a pointer. In fact, iterators are an object-oriented approach to pointers: they allow you to traverse ranges regardless of any structure that might exist “behind the scenes”. Pointers allow you to do that as well, but only if there is no structure to the range – i.e. if the range is a contiguous chunk of memory. Iterators allow you to hide the structure of the underlying range and allow you to traverse it efficiently regardless of that structure.

Iterators are not unique to C++, but the specific implementation of iterators we find in the STL and the categorization of iterators we find in the C++ standard is unique to C++. Aside from the iterators found in the STL, several other implementations exist. In fact, Boost has a whole library of iterators and there is a proposal, from its authors, to radically extend iterator concepts.

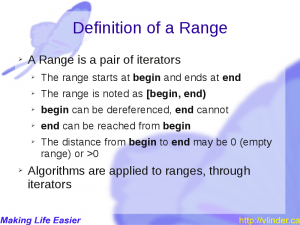

A range is, basically, a pair of iterators, one of which is at the beginning of the range, and one of which is one past the end of the range. If the range is not empty (i.e. begin != end) the iterators in the range [begin,end) can all be dereferenced, and are all valid. end is valid, but cannot be dereferenced.

For any valid range, end can be reached from begin, but the inverse is not necessarily true. For example, if the range is a single-linked list, traversal using iterators may be a question of reading the next pointer of the node pointed to by the iterator (for all you know, the iterator might be the node itself, or a thin adapter of the node). As the node has no prev pointer, going from the end to the beginning may not be possible. Often, end is a “magic” iterator in that it contains a flag saying it is “at the end”. Such iterators can be constructed in constant time on structures such as a single-linked list, because they don’t have to traverse the list – but it will be all the more impossible to find any iterator that points inside the list from such a “magic” iterator.

The number times one has to increment an iterator to go from begin to end is called the distance between begin and end. That distance is 0 for an empty range.

The STL algorithms apply to ranges, which are accessed through iterators.

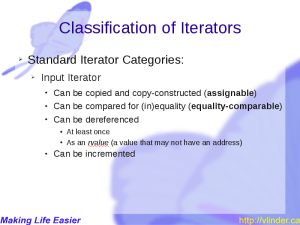

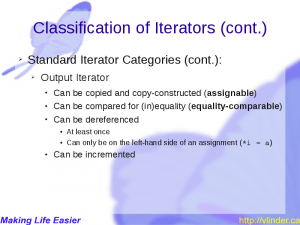

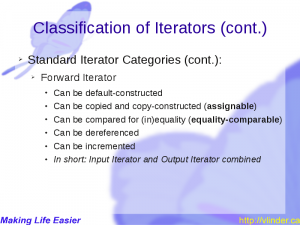

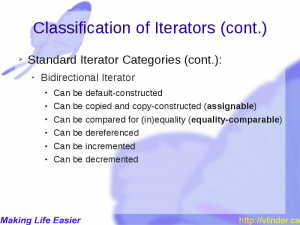

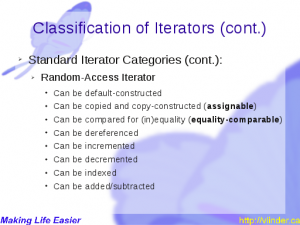

Several standard categories of iterators exist: input iterators, output iterators, forward iterators, bidirectional iterators and random-access iterators. We will take a look at each of these categories.

Input Iterators are iterators that you can read from once before you increment it, which you can do once before reading again. The istream_iterator is a good example. Such iterators are used to read from streams such as files, the standard input device, network connections, etc. Generally, the end iterator for these is a “magic” iterator: it is a default-constructed iterator of the same type.

Output Iterators are similar, but are written to in stead of read from. Often, they point to output streams and writing to them can send data to a file, over the network or to the standard output device.

Like in the case of input iterators, the end iterator for output iterators is usually “magic”, though it is far less useful than the equivalent magic input iterator: while it is often important to read all input, the output is produced rather than consumed, so it is the program itself that knows when it is at the end – when it stops producing.

Forward Iterators are a kind of combination of Input Iterators and Output Iterators: they can be incremented and both read from and written to. Unlike Input Iterators and Output Iterators, you can dereference a Forward Iterator more than once between incrementing, and increment it more than once between dereferencing.

Examples of Forward Iterators are iterators of single-linked lists.

Bidirectional Iterators have all of the features of Forward Iterators but add the ability of reverse iteration - i.e. they implement a -- operator allowing both forward and backward traversal of the range.

Examples of Bidirectional Iterators are iterators of double-linked lists and associative, tree-like structures.

Random-Access Iterators have all the features of Bidirectional Iterators, but add the possibility to efficiently add an subtract - i.e. you can advance the iterator in (large) steps and efficiently calculate the distance between two iterators in a range.

Examples of Random-Access Iterators are pointers that point inside an array, or vector iterators.

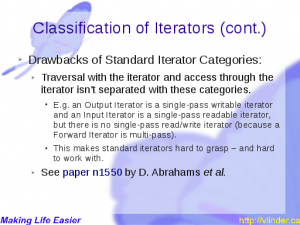

If you have paid close attention, you will have noticed something odd: the standard iterator categories change in two aspects from one category to the next. For example: Input Iterators can be read once between increments, and increment once between reads. Forward iterators can be read and written, both any number of times, between increments, and can be incremented any number of times between accesses. That means that from Input Iterators to Forward Iterators, both the rules for traversal and the rules for access change. David Abrahams et al found the same thing and wrote an article, and proposal, to fix it.

This bug – I do think it’s a bug – in the standard makes standard (STL) iterators harder to work with than necessary, and hard to explain: they tend to confuse people, which is never a good thing. The Boost.Iterator library goes a long way toward fixing this, by introducing separate concepts for traversal and access.

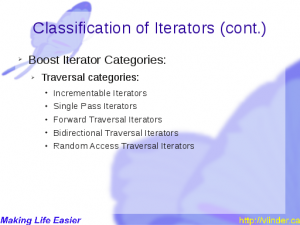

The Traversal Categories define how the iterator traverses the underlying range: whether you can pass over the range (with the same iterators) more than once, whether you can go forward and backward, and whether you can skip over values or not.

Of course, all iterators are Incrementable – they wouldn’t be much use otherwise – but some iterators may allow you to pass more than once over the range while others – e.g. classic Input Iterators – may not, etc.

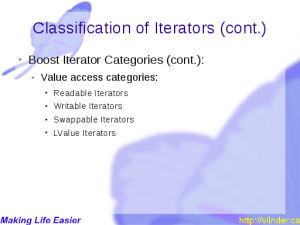

Similarly, Value Access Categories define how the iterator is dereferenced and what dereferencing yields: an lvalue reference to the pointed-to object, a proxy, a read-only object, etc.

Splitting these concepts allows a much finer-grained definition of the requirements of algorithms – e.g. an algorithm might need single-traversal readable iterators, or might need incrementable lvalue iterators: neither combination is possible within the current standard iterator traits.

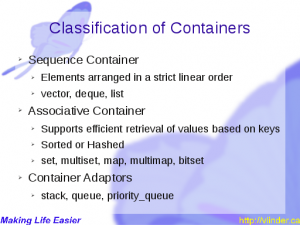

Iterators point to elements of a range and those ranges are usually encapsulated in a container. Different flavors of containers exist: sequence containers have their elements arranged in a “strict linear order” – i.e. one element follows the next; there is no implicit sort, etc. examples of these are vectors.

Associative containers allow access to the elements in the container using a key and usually store the elements as a key-value pair (but not always: bitset, for example, doesn’t do that). The order of elements may or may not be linear, and is determined by the key, rather than by the order in which the elements are added to the container.

Container Adapters aren’t really containers but pretend to be by adapting the underlying container and adding an API abstraction to that container. A stack provides a single-ended queue abstraction to a double-ended queue, for example.

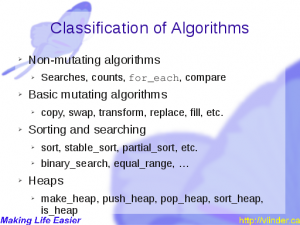

Because of the way iterators are classified, it is not possible to classify algorithms in the same way, by simply defining what kind of iterators they need to work on. The iterator categories are used to determine how algorithms can be optimized, however.

A good example of how algorithms can be optimized according the the category of the iterators used with it is std::advance: it requires a Forward Iterator to work but works more efficiently with a Random-Access Iterator, where std::advance(iter, n) can simply do iter + n, whereas for forward iterators (and bidirectional iterators), advance looks like a for loop.