The Art and Science of Risk Management

I like to take a rational approach to risk management: identify risks and opportunities, their probability and their impact, maximize the impact and probability of opportunities and minimize those of risks. In this article, I explain a bit of my approach, I expound upon risk dependencies, based on a recent article by Tak Wah Kwan and Hareton K.N. Leung, and I offer some practical advice.

Introduction

Risk management is a central part of project management – or at least, should be. It is one of the things that makes software development an engineering discipline, rather than a hobby. Several issues persist in day-to-day risk management, however:

- risk management is rarely specifically addressed in agile methodologies

- effective risk management requires more effective and open communications than usually prevelent in software development teams

- the (recurring) stages of risk management are well-documented but not widely understood

- risk dependencies are often overlooked

- severity metrics are often over-simplified

In this article, I briefly touch on each of these subjects: I first define risks and opportunities, what they consist of and what their life-cycle looks like; I highlight a few common areas of risk; I analyze the risk dependency management method proposed by Kwan and Leung, offering some critique on its restrictions; and I propose a novel way of quantifying risk severity.

Risks and Opportunities

Risks and opportunities are inherently the same thing: they’re events that may happen during the project life-cycle that have an impact (positive for opportunities, negative for risks) on the project’s execution or outcome.

Risks consist, when they are documented, of six things:

-

Severity

-

Probability

-

Impact

-

Synopsis

-

Purpose of response

-

Action Items

The severity is a function of the probability and the impact, and can be calculated automatically - we’ll look at the possible formulas for calculating this further down.

Risk Life-Cycle

Figure 1: The SEI Risk Management Paradigm1.

The Software Engineering Institute specifies five phases to risk management23:

- Identify project risks

-

Analyze: evaluate and prioritize project risks

-

Plan: develop risk response plans

-

Track: monitor status of risk and associated risk response actions

- Control risk response actions

As noted in every source you might read on the subject, risk management is a continuous process that starts at the inception of the project and never ends as long as the result of the project is maintained. As ISO 31000 puts it4:

For risk management to be effective, an organization should at all levels comply with the [following principles]:

- Risk management creates and protects value (...);

- Risk management is an integral part of all organizational processes (...);

- Risk management is part of decision making (...);

- Risk management explicitly addresses uncertainty (...);

- Risk management is systematic, structured and timely (...);

- Risk management is systematic, structured and timely (...);

- Risk management is tailored (...);

- Risk management takes human and cultural factors into account (...);

- Risk management is transparent and inclusive. (...);

- Risk management is dynamic, iterative and responsive to change (...);

- Risk management facilitates continual improvement of the organization (...).

In agile projects, this means that risk management implies every person who works on the project: stakeholders as well as developers – pigs as well as chickens.

For risk management to be effective, a work environment that is open to communication should be cultivated: without effective communication, risk management cannot be effective either.

Identify

Risk identification involves any-one from the CEO to the intern: when the first business case is set up for the project, the first risks should be identified and tracked. From then on, any-one working on the project should be expected to provide input where risks are concerned: if an intern doesn’t understand why a given component depends on another – however innocuous that dependency might seem – he should be encouraged to talk tohis team leader about it, they should look for any risk the dependency might cause and the reason for the dependency to exist, and both should be recorded.

Analyze

While the initial analysis of a risk may be done by the analyst or the project manager, she should be open to (constructive) criticism – especially from the person who first identified the risk. Any part of the analysis, especially the part that leads to conclusions on the probability or the impact of the risk, should be well-documented, justifiable and open to scrutiny.

Plan

Once a risk has been identified and analyzed, some-one has to decide what to do with it: attempt to mitigate/exploit, or ignore? That decision, too, should be open to scrutiny as the project continues, as both the impact and the probability of a risk can change over time, as can the feasibility and cost of mitigation/exploitation.

In order to plan for mitigation/exploitation or ignoring, one first has to define what would need to be done to mitigate the risk/exploit the opportunity. If you’re using an action item database, the action items should be created regardless of whether the risk will be mitigated/exploited and keeping in mind that it might not be, and each action item should be assest for feasibility and cost.

Track

During the rest of the project’s life cycle, it is the project manager’s job to keep track of the risks: how the associated action items are planned and coming along, whether the probability or impact of the risk has changed, etc. Any changes in these parameters should cause new action items to be planned - which is what control is about.

While it is the project manager’s job and responsibility, that doesn’t mean that other team members shouldn’t involve themselves: if they have a worry about, or an involvement in, a given risk, they should feel free to monitor it. This implies that the monitoring data should be freely available to team members (including stakeholders).

Control

Controlling, in risk management, is basically taking the output from tracking and re-iterating planning with the new data. Again, this should be an open and transparent process: any input should be welcomed and encouraged.

Areas of risk

The risky parts of a project depend very much on the project, so there isn’t much that can be said about this in general, if not that the most overlooked risks are usually in the assumptions made when designing the solution: every assumption can become a risk.

As an example: some of the firmware I recently worked on made an innocuous assumption in the code. According to the code, no single version of the firmware would have more than sixteen (16) revisions. This assumption was implicit in encoding the revision number as a four-bit integer. Of course, more than a year into the project, this assumption, which wasn’t documented anywhere, became a bug as the seventeenth beta version of the firmware refused to install.

Over the years, I’ve run into countless seemingly innocuous assumptions that became bugs: they are inevitable as it is impossible to take every possibility into account. Still, some such assumptions can be easily seen as false. For example: in a system that is designed to be operating 24/7, a 32-bit timer that counts milliseconds will overrun in less than 50 days. It generally isn’t very expensive to use 64-bit counters for such timers, and it buys you another five-hundred and eighty-three million years. Suffice it to say that the warranty will probably have expired by then.

In most risk assessment models I’ve come accross, risks are synonymous with failure: risk analysis methods look at the failure modes of the project’s result or the product being worked on. Although these risks are valid and should be analyzed, they are often far less costly than unmitigated risks early in the development cycle. For example: if you’re integrating a system with a printer and you have to write your own driver for that printer, you will soon find out that the printer’s documentation and its actual behavior are often very far apart. The same is true for many devices you might have to use. While the vendor’s drivers usually do an OK job, they might very well not exist for your platform and, in most cases, source code will not be available. If you run into such problems late into the development cycle, when having the hardware integrated with your firmware or software may become a bottleneck, your entire project may be delayed (and therefore become more costly), deadlines may be missed (and customers lost), etc., just because the integration was assumed to be low-risk. This has nothing to do with failure modes - at least not with failure modes of your product - and is therefore often overlooked in risk analysis.

Risk dependencies

One issue that has, in my experience, always been overlooked is the possible dependencies between risks. Kwan and Leung address this in their article “A Risk Management Methodology for Project Risk Dependencies”, to be published in IEEE Transactions on Software Engineering.

In their article, they specify a method for risk dependency tracking and risk management that restricts risk dependency to “an effect due to the occurence of a risk and this effect can either increase or decrease the probability of the occurence of other risk(s)”5. I.e. risk dependencies are restricted in two ways in this model: if risk $R_a$ is a Direct Predecessor of risk $R_b$, and risk $R_b$ is a tuple of the probability of the risk occuring, $P_b$, and its impact, $I_b$, the occurrence of $R_a$ changes the probability $P_b$, but not the impact $I_b$. The reasoning for this is the following: “as each risk [is a tuple of] the Probability $P$ and the Impact $I$, for the case of $R_a \to R_b$ if $R_a$ occurs, the risk dependency may have an effect on either $P_b$ or $I_b$ of $R_b$. At a given time, if the impact estimations are done correctly, the impact of $R_b$ should already have considered the effect of other risks. It will not need to be changed even if we add the risk dependency.”. This reasoning presumes that the impact of a risk cannot be compounded by the occurence of the risked event of another risk. Such is, in my opinion. clearly not the case. As a counter-example, the proximity of two components on a PCB may cause the components to overheat or may cause short-circuits. While individually these two risks may cause minor damage, the overheating and the short circuit together may compound and cause a fire. Each of these risks does not increase the probability of the other, but they do increase each other’s impact.

The second restriction is in the fact that the $R_a \to R_b$ dependency is only “activated” when $R_a$ occurs. However, by the relation itself, it can be inferred that any increase in the probability $P_a$, $P_b$ must also change, so the dependency relation $R_a \to R_b$ implies a dependency relation $P_a \to P_b$. The same is not necessarily the case for $I_a \to I_b$ or $P_a \to I_b$, however.

The two restrictions greatly simplify the model and probably made the case studies for their research feasible. Among other things, they have the effect of rendering the directed graph they define as the Risk Dependency Graph acyclic: if only the occurence of a risk $R_a$ triggers the dependency, the probability $P_b$ remains independent of probability $P_a$ even if $R_a \to R_b$ and both $P_a$ and $P_b$ can be assessed independently. The same is not true if $P_a \to P_b$, in which case it becomes impossible to asses $P_b$ independently from $P_a$ and in which case the directed graph becomes artifically acyclic in order to be able to assess the probabilities of each risk.

Regardless of, or perhaps because of, these restrictions, their model is certainly useful: they define useful methods to define dependency values, by defining a Risk Dependency Value and a Risk Dependency Multiplier, which can be used to calculate the new probability of the dependent risk and which produces the new risk $R^{+a}b=f(P^{+a}_b,I_b)=f(P_b+D{ab’}I_b)$ where $P^{+a}b\in P$ or $R^{+a}_b=f(P_b DM{ab’},I_b)=f(P_b+D_{ab’}I_b)$ where $P_b DM_{ab’}\in P$6.

They also provide three methods of compounding multiple dependencies - i.e. scenarios in which $R_p \to R_s$ and $R_q \to R_s$ and $R_r \to R_s$ and $P_s$ needs to be calculated. The three methods, dubbed the Conservative Method, the Optimistic Method and the Weighted Method7 are well-considered and explained, including their advantages and drawbacks.

They also provide clear and concise matrices to apply their method of risk dependency assessment and to give guidance for risk dependency action plans. These matrices and guidelines are potentially very useful, especially when combined with the proposed metrics for analyzing (posterior) risk and response effectiveness8. Evidently, I will not reproduce them here - you should read the article in IEEE Transactions on Software Engineering.

Calculating Risk Severity

Calculating the severity of a risk should take into account both the probability and the impact of the risk’s occurrence. The probability is a number between 0 and 1; the impact is measured in dollars. Often, this is noted as $S=f(P,I)=PI$, meaning the severity $S$ is the product of $P$ and $I$. While this is doubtless the most common way – and certainly the most intuitive way - of calculating the risk severity, I don’t think it’s the best way. For example, this way of calculating severity assigns the same severity to a 1% chance of losing $100 as it does to a .0001% chance of losing $1,000,000 – that is, a one-in-a-hundred chance of losing one hundred dollars and a one-in-a-million chance of losing one million dollars. However, losing $100 is usually an acceptable loss, whereas losing $1,000,000 could be devastating to the project - or to the business.

I therefore propose a different approach, weighing the impact exponentially heavier than the probability. In this approach, the formula for the severity looks like this: $-\frac{1}{\log(P)}I$, which gives the 1% chance of losing $100 a severity of 50, while it gives the one-in-a-million chance of losing $1,000,000 a severity of 166,667. An approach like this, in which the impact is weighed exponentially heavier than the probability, takes into account the fact that even a very slight chance of catastrophic failure must be taken into account and the resulting risk must be mitigated. Similarly, a slight chance at a great gain must be taken into account and the corresponding opportunity should be considered.

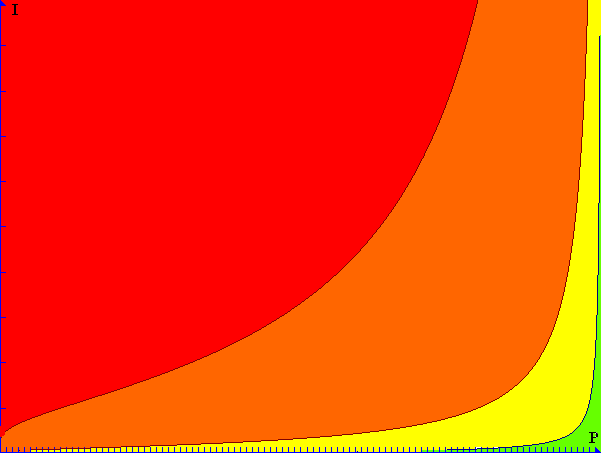

Figure 2: Severity in relation to Probability and Impact

As shown in figure 2, using this method allows for a perhaps more intuitive approach to severity: small losses and small gains are considered far less interesting than large losses or large gains, even if they have a high probability of occurring (in this graph, I ranges from 0 to 1,000,000). Of course, the severity values to be considered “very high”, “high”, “medium”, “low” or “very low” are somewhat subjective and may vary from project to project.

The priority assigned to any risk is not necessarilly the same as the risk’s severity: although it may be coupled to the severity, it may also be something of a gliding scale, dependent perhaps on the feasibility and cost of mitigation. For example, if a million-dollar impact risk has a chance of one in a million of occurring but only costs one dollar to mitigate, it may be worth mitigating whereas if that same risk would cost a million dollars to mitigate, mitigation is as costly as the possible risk itself.

Conclusion

Risk management is an important part of the software engineering practice and is certainly compatible with agile methodologies. Risk dependency management enhances existing practices and the methods proposed by Kwan and Leung form a welcome addition to the methods currently available for risk management.

Quantifying risk severity using the proposed method can further enhance risk analysis and planning, thus improving project outcome.

-

R Williams et al, “Putting Risk Management into Practice”, IEEE Software 14(3), 1997, pp. 75-82. ↩

-

ibid. ↩

-

Kwan et al., “A Risk Management Methodology for Project Risk Dependencies”, IEEE Transactions on Software Engineering 99(preprint), 2010 ↩

-

“Risk management – Principles and guidelines”, ISO/FDIS 31000:2009(E) ↩

-

ibid. note 3 ↩

-

ibid. ↩

-

ibid. ↩

-

ibid. ↩